Meet the FAS faculty: Jessica Thompson

When did people first evolve into the modern humans that we are today? What instigated the changes that differentiated humans from chimpanzees and other primates? The average person may not consider these questions, but Jessica Thompson is figuring out life’s mysteries one animal fossil at a time.

To nominate an FAS faculty member to be featured in this series, please email fas.dean@yale.edu.

When did people first evolve into the modern humans that we are today? What instigated the changes that differentiated humans from chimpanzees and other primates?

The average person may not consider these questions, but Jessica Thompson is figuring out life’s mysteries one animal fossil at a time.

Thompson is Assistant Professor in the Department of Anthropology in the Yale Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) specializing in paleoanthropology, the study of human origins and evolution. Like many of her FAS colleagues, her work is motivated by curiosity about the world around us, and it asks and answers new questions about the nature of human life.

Thompson’s interest in the field began with an undergraduate biological anthropology course at Washington State University led by late anthropology professor and bigfoot hunter Grover Krantz.

“He made this really big impression [on me] because I felt like you can really, at least try to approach things scientifically that might seem really strange, and that was kind of appealing to me,” she said.

Since then, she’s made a large imprint on the field, first through two post-doctoral positions at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, then as an Assistant Professor at Emory University, before coming to Yale in 2019.

Her work focuses on understanding the origins and trajectory of modern human evolution. To do this, she started a field project in Malawi in 2009. The project focuses on southern eastern Africa because of the lack of formal academic research in this important area for understanding human origins, and she continues to conduct research there every summer.

“The [area] that links southern Africa to eastern Africa was not really very well-known and I knew there had to be sites there that would help address some of these questions,” she said.

While there is scientific consensus that ancestral human populations first arose in Africa, a lot of anthropological work has been done through a Eurocentric lens and focuses on Neanderthals, which Thompson described as a “sister” or “cousin” to modern humans and not direct relatives.

Paleoanthropology gained popularity in Europe; European scientists interested in their origins looked for evidence in nearby caves. Europe is known as a source of human fossils, artifacts made from bone, and art, because it has a geological advantage: caves allow for better preservation. In contrast, it’s harder to recover these things in Africa where there are fewer caves giving shelter to them, Thompson explained.

“It makes it easier to study human origins in a place like Europe where you have better preservation, but then also a much longer history of interest in it as well,” she said. “And then the consequence is that we know a lot more about Neanderthals, which aren’t even really our ancestors, than we know about ourselves and our own evolution.”

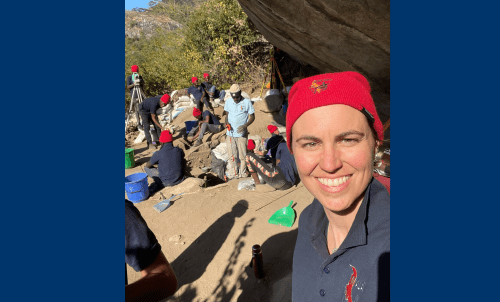

Thompson pointing to a fossil bone covered in a sandy crust from the sediment that surrounded it at the site. Each artifact is numbered and placed within a corresponding plastic bag, which is later entered into a database in Thompson’s lab and easy to locate for future researchers.

After starting a project in northern Malawi that suffered from this problem – millions of stone artifacts preserved on a landscape with no associated fossils – Thompson has focused her recent efforts on looking for makeshift overhangs and shelters for better quality remains. This has had recent success over the years, including discovery of shell beads, fossils that point to major shifts in ancient environments, and some of Africa’s most ancient human DNA.

For Thompson, anthropology not only involves discovery but also collaboration. She works to make research accessible and inclusive of local populations.

“One of the brilliant things about it is we’re living in villages in communities of people, just the way that they live. We’re not renting out some palace in the middle of a rural community,” she said.

One of Thompson’s many objectives is to increase local outreach. At every field season she has a person dedicated to going into communities to describe the research being conducted. Local schools sometimes organize visits to the sites where she is working, where she leads a crew drawn mainly from local families. Her end goal is to contribute to a sustainable heritage research infrastructure in Malawi, but for this effort to be effective over the long term requires more consistent funding and support for education of people in Malawi than is available under a typical research grants model.

Not only does Thompson handle the excavation and research related to recovered artifacts, but she also takes on logistical tasks such as securing visas, arranging the inventory of supplies, and coordinating itineraries. These other tasks can limit the amount of time she can devote to research. Students who want to gain field experience do so for free, as field projects in archaeology aren’t awarded enough money to pay students. This can limit which potential future professionals can participate.

“If you’re looking at people who have to be able to afford to take a summer off and go do a field experience and not get paid for it while they still have rent at home to pay, you’re automatically filtering out a lot of people who might be very interested,” she said. Thompson is leading an initiative across FAS to develop a workshop in Spring 2024, hosted by the Yale Peabody Museum, that will address these issues.

Thompson also tries to ensure that as much funding as possible flows into the communities that make this work possible, but it is seasonal in nature. The lack of long-term investment in infrastructure and personnel limits the ability to establish truly sustainable models of locally-led research in which Thompson might act as more of an advisor. This in turn limits the duration of time the field site, artifact preparation, and analyses can operate.

“[So] much has to go into generating the science that is logistical and also community based. There has to be that reciprocal relationship with the communities where you’re working, because otherwise we shouldn’t be there.”

Despite these challenges, Thompson remains hopeful and believes that enough attention drawn to the issue can bring about reforms that make paleoanthropological research more accessible, and the role of people in local communities more visible.

“Africa is where it started, and if we want to do that work then we need to be realistic about how important it is to involve people who already live there.”