Facts and Fabrications: FAS Professor Explores Worlds Created by Print

In her new book, Paola Bertucci, Professor of History and History of Science and Medicine in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, explains how fictionalized scientific facts can become reality for readers – in the eighteenth century as well as today.

By Natalie DeVaull-Robichaud

In the middle of the pandemic when the controversy over vaccine safety and fake news was at its height, Paola Bertucci revisited her first book – written in Italian and focused on an 18th century medical controversy – and realized the histories she had uncovered could illuminate the present moment.

“Reading about the debate on vaccines, misinformation, and disinformation brought back to mind the medical controversy at the core of my first book. I realized that I could rework it to highlight the fabrications that both parties involved in the controversy created on the printed page. I wanted to show that the eighteenth-century reading public faced challenges similar to those that we face today when it came to assessing what to believe of all the stories they found on the printed page. I also wanted to show that eighteenth-century scientists used the medium of print to present an enhanced version of themselves and their work. In other words, they cared for the equivalent of today’s digital presence: how they appeared on the printed page,” Bertucci explained.

The controversy centers around the famous French physicist Jean-Antoine Nollet and the relatively unknown Italian scholar Gianfrancesco Pivati, who declared he’d invented a “cure-all” using electrified tubes. Nollet embarked on a journey to Italy to challenge Pivati’s claims in what would be hailed as a “philosophical duel” but was, in fact, something else entirely.

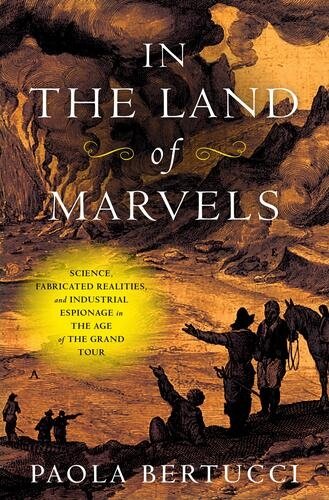

Bertucci’s new book, In the Land of Marvels (Johns Hopkins University Press), draws from private documents to reveal the manipulations of information surrounding the published report of Nollet’s journey. She spoke to Natalie DeVaull-Robichaud of the FAS Dean’s Office about her discoveries.

It took years of research to discover the letters that Nollet sent to the French State when he was in Italy. Could you speak about the discovery you made and why the pandemic was the right time to write this book?

Paola Bertucci: What I discovered is that there was something else that motivated [Nollet’s] journey, which was the gathering of technical information on the silk industry. Silk was a valuable commodity in the eighteenth century, and northeastern Italy exported silk threads all over Europe. Many states tried to imitate the Italian production, without success. France was eager to establish production of Italian-style silk threads to support the great industry of silk textiles in Lyon. So Nollet was actually an envoy by the French State on a secret mission to collect usable information on the manufacture of silk threads. When Nollet is back in France, he presents his journey to Italy as motivated by his desire to assess the truth about the miraculous cure of Pivati and other Italians. In print, he fabricates the story of his encounters with the Italians as an open-ended philosophical duel during which they performed experiments together to find out the truth. In fact, he had already decided that the Italians had made up the results. But what’s interesting is that the Italians who [claimed] the miraculous properties of electricity in curing diseases were also deliberately fabricating experimental results, and so I was interested in how, once in print, these fabricated stories became reality for readers. And this is really the parallel that I saw during the pandemic between what was going on in social media, in the cyber sphere, and the world created by print where 18th-century readers were absorbing facts that never happened.

So how can historians be sure they aren’t accepting fabricated realities as facts?

Bertucci: My book uncovers various levels of fabrications, which begs the question you are asking. When you walk into a library or an archive and you find historical sources, you cannot be sure that they are telling true stories [just because] they are older. It is easy to fall prey to the fabrications of these early authors because we don’t speak the same language – in the sense that we don’t partake of the same culture, and so we can easily miss their internal jokes.

There are studies that discuss the silence of the archives. They point out that what is preserved represents the structures of power that were in place at the time, and so historical figures we have an interest in may be completely absent in the archive, even though they were present and relevant in their own time. Scholars of slavery, for example, [have] done a lot of work on this topic. They ask the question: how do you use the archive against itself, against its own intention?

My case was the opposite, as I didn’t find silences in the archives. My archives spoke very loudly, pulling me in one direction and the other. I loved the story of this medical controversy because the many sources enabled me to see all the various fabrications as they were created. One lesson that I learned is that one archive is never enough, and we often need to cross-reference. Fake news [has] been around forever, it isn’t an artifact of the digital world. Manipulating information to embellish or fabricate realities is an ever-present human endeavor that I find fascinating because it makes me reflect, as a historian, on the delicate distinction between history and fictional story-telling. Don’t expect that the older fabricators [will] be easily spotted or identified! One famous 18th-century author published a text entitled The Charlatanry of the Learned to warn readers about the fabrications authored by scholars and scientists. The question “what to believe and why” is not a new one.

The word “marvels” in your title evokes the impossible, fabrications – an idea of a place that isn’t in line with reality. How did you choose In the Land of Marvels for your title?

Bertucci: That’s a metaphor for Italy. In the eighteenth-century Italy was a travel destination just like today. It was the age of the so-called Grand Tour, when the learned elites in Europe, especially Northern Europe, traveled to the southern European countries for an experience that would transform them. In this travel literature you find a lot of emphasis on Italy as a place of marvels. [They] were marvels of art – for example the masterpieces of Renaissance art – and they were marvels of nature, like the only active volcanoes in Europe or the bioluminescence in the Venetian laguna. So, in travel literature you find the idea of traveling through Italy to see something that exists only there and that is beyond expectations.

And what is interesting is that this literature creates the idea of Italy when Italy doesn’t exist, because in the eighteenth century there were several little states, there was no Italy as a political entity. So again, print creates an imagined reality of one country that is not there. It also creates and circulates stereotypical representations of Italians as “lovers of the marvelous,” or in other words, unreliable, credulous individuals who deceive themselves and others. I show that Nollet builds on this pre-existing stereotype to cast the “philosophical duel” between himself and his Italian counterparts as a battle between his love of Truth and their love of the marvelous. The eighteenth-century reading public loved to adjudicate controversies they learned about in print, just like it happens today on social media. These controversies, again like today, were sometimes entirely fabricated and survived in the readers’ imagination even when they were debunked.

What does your book teach us about scientific truth today?

Bertucci: What this story tells us is that it is difficult to separate the science from the humans that make it, which is a basic lesson from the history of science as an academic discipline. More specifically, though, the story at the core of my book also points to the fact that it is hard to tear apart truth from belief. This, combined with the historical reality that fabrications also occur in the world of science, means that more emphasis on the process of science as a human endeavor, and not just on scientific results, would serve the public better than an acritical defense of scientific truth.

Paola Bertucci is a Professor of History and the History of Medicine in FAS. Her book, In the Land of Marvels, is available from Johns Hopkins University Press.

The FAS Dean's Office announces new books to the FAS community and beyond. FAS faculty can inform us of their book’s publication through this webform.