Transcending National and Literary Boundaries: Persianate Poetry in World Literature

FAS Assistant Professor Samuel Hodgkin’s new book shows how the classical Persianate canon shaped the poetry of revolution across modern Eurasia.

Samuel Hodgkin was studying Central Asian history when his academic plans abruptly changed.

In the process of learning Persian to read sources for nomad history, Hodgkin was immersed in Persianate poetry – an experience that turned out to be transformative.

“The sense of direct encounter with other minds in distant times was such an exciting shock that I ended up getting completely absorbed in the poetry,” Hodgkin said. “When I went to grad school at Chicago, it was Persian poetry that I wanted to keep reading and thinking about.”

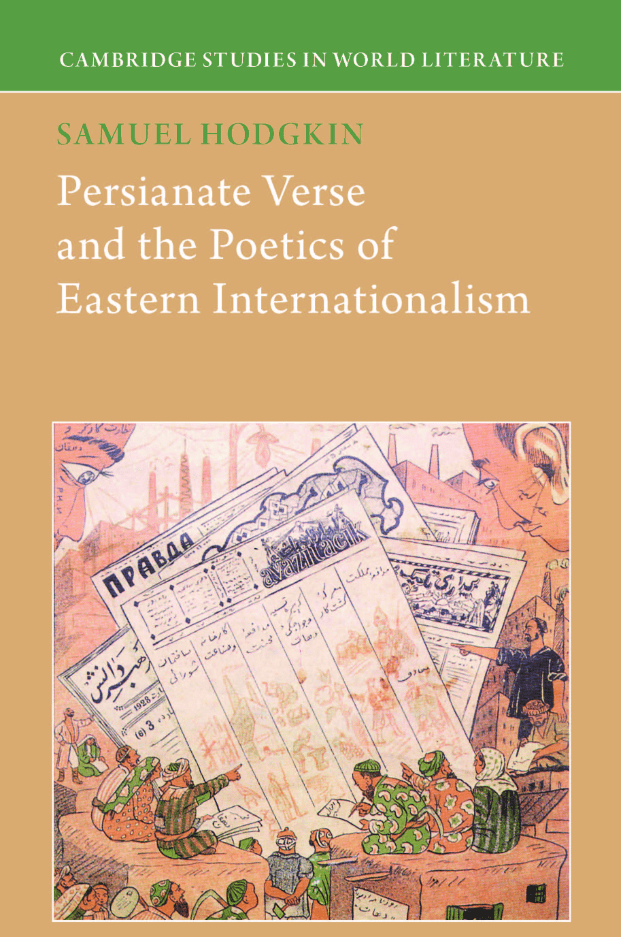

In Persianate Verse and the Poetics of Eastern Internationalism (Cambridge University Press), Hodgkin explains how Persianate poetry came to be a unifying artform for writers from Soviet Central Eurasia, South Asia, and the Middle East. The literature written under communism was profoundly influenced by classical Persianate poetics; in fact, classical Persianate poetry continued to impact non-European poets beyond the end of the Cold War. Hodgkin said that even today, Persian poetry shapes literature as well as popular culture in Russia, Central Eurasia, and the Middle East. But with a few exceptions (Hodgkin mentioned the Turkish poet Nâzım Hikmet and the Urdu poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz), these exciting leftist poets remain outside the Western canon of world literature, read outside their own languages only by area studies scholars.

In writing Persianate Verse, Hodgkin explained that he hopes to “deprovincialize these poets I cared so much about by returning them to the big wide revolutionary world for which they wrote.”

Samuel Hodgkin, Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, spoke with Natalie DeVaull-Robichaud of the FAS Dean’s Office about his new book, non-Eurocentric perspectives on world literature, and the enduring popularity and influence of Persianate poetry.

How is Persianate poetry viewed today?

Hodgkin: It depends a bit where you are. In the West, where Persian poetry was massively popular in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, its visibility has really receded. In Western China and in India, the persecution of Muslims has been disrupting the transmission of Persianate poetic traditions. But across much of Eurasia, the story is overwhelmingly one of continuity. It's hard for a lot of first language English speakers to understand the popularity that poetry has in so many of these societies, in which, for every published poet, there are many regular people who might never publish anything that they compose, but [who] play poetry games with their friends, have vast swaths of poetry memorized, sing it, listen to it while they're driving around, and engage with it in a variety of ways. Pop music in the Middle East and in Central and South Asia has often drawn its lyrics from classical poetry or poetry written in classical forms. There are also plenty of modernist or postmodernist poets who write to varying degrees in conversation with Western or sometimes East Asian poetic forms and for whom the Persian classics are not necessarily an important reference point. But at the popular level the classics are very much alive.

Can you talk a little about how the Persianate literary forms keep a shared sense of cultural heritage alive?

Hodgkin: There are a few stages to the story. The generation of madrasa-trained writers and writer-activists come to these struggles not with some idea of the classical Persian heritage but with that being the rhetorical toolkit at their disposal; for them, poetry is an important language of exhortation and persuasion. Satire is a traditional Persianate poetic repertory, so when they want to make things happen, they write poetry for newspapers and incorporate poetry into their speeches.

Then in the 1920s and 30s, [there is a] reaction among a younger generation of proletarian writers and critics in the Soviet Union, Turkish nationalist writers in the Republic of Turkey, and modernizers in Iran and Afghanistan, who start to say: We need a fundamentally different relationship to language in which there's really no place for the classical aesthetics that informed the previous generation. You can't build a new world with this old, ornamental language. In Turkey, they start removing Persian and Arabic words from the language and replacing them with these folk or pseudo-folk Turkic words. (That started earlier, but this is when it got state backing.) In the Soviet Union, there's an attempt to build an alternate literature for these communities out of oral genres. And what you see in the 1930s period of statist authoritarianism, all over Eurasia, is a kind of return to the classics as a heritage object for its prestige and for its aesthetics of hierarchy and contained difference. That is a peak of what we might think of as Persian neoclassicism. It's a nightmare in terms of poetic ethics, and also for the most part a dead end artistically.

And then the third moment in this story is a kind of afterlife in which the Persian classics, classical Persian genres, and ways of being sociable through literature are brought back by writers who are brought together not by state institutions but by political affinity and shared aesthetic projects. And so you get lots of movies that quote Persian poetry and do fun, playful, strange things with it. You get poets who don't write in classical genres but write with the classics in various ways.

Can you describe the role of Persianate classics in terms of “world literature”?

Hodgkin: The culture wars in the US and in the English-speaking world, since the 1980s, have been animated by some questions that were also the vital questions among communists in the non-West and among cultural bureaucrats in the Soviet Union, in the interwar period. How do you take the Western category of literature and build a cross-cultural canon that takes non-Western works and genres as seriously as Western ones? What are the representative functions of non-Western texts in such a canon? How do you deal with problems of tokenism? What about the class origin of texts, as a different kind of representation than cultural diversity? These are all questions that were very important to the mid-century writers and critics that I deal with in this book. As I build syllabi for undergraduates at Yale, I'm acutely aware that these problems did not arise recently but are things that people have been grappling with and proposing interesting pedagogical solutions to for a long time.

What impact did these Soviet literary organizations have on the Persianate poetry you discuss in your book?

Hodgkin: Its first effect was to give a bunch of new rhetorical functions to poetic genres that had always been in service to one function or another. And this, of course, produced all sorts of new aesthetic operations. A panegyric that praises the masses—or Stalin—will of course do different things than a panegyric for a ruler. Likewise, a poem disseminated in a newspaper is going to play with its setting just as a poem recited at court gestures towards its quite different setting.

The introduction of Persian poetry into the Soviet literary bureaucracy [also] massively magnified its potential audiences, especially in translation. Poems produced in this system and their authors were often judged and disseminated more widely or less based on their reception in Russian or sometimes in other languages. This meant readerships that assumed they could judge the aesthetic merits of poetry in translation decided the fate of those poets more than the audiences that could actually hear and read the poems themselves. It incentivized certain kinds of writing. But, frankly, rather than a bunch of poetry written for translation, what that system mostly produced is poems that did all sorts of wonderful things that most of their readers couldn't appreciate. Russian intelligentsia readers couldn't appreciate a poem in defense of a persecuted Yiddish language director that pursues that defense through a series of exquisite allusions to Rumi.

If we're interested in learning more about the Persianate classics, where would you suggest we begin?

Hodgkin: Geoffrey Squires’s translations of Hafez and Franklin Lewis's translations of Rumi are a great place to start. There's still not nearly enough of the best Persianate poetry in translation in English.

What would you like readers to take away from this book?

Hodgkin: Beyond academia, I very much hope that this book will make its way into the hands of many of the Middle Eastern, Central Asian, and South Asian activists and people for whom this history and this literary tradition remain vitally important.

At Yale and in America, I hope this book can function as an incarnation of some other possibilities for what we might have as readers if we expand our minds beyond the English literary world. In Anglophone America, the Venn diagram of readers and writers of poetry beyond the classroom is a small circle, and that's not true at all in the wider world. Outside English, poetry is still a revolutionary force! Even today, there is still far more poetry being written and read by mass literary communities in the world that I document in my book, and they write and read so much partly because they believe poetry really can make things happen, that it has a special toolkit for changing the world.

Samuel Hodgkin is Assistant Professor of Comparative Literature in the FAS. His new book, Persianate Verse and the Poetics of Eastern Internationalism, is available from Cambridge University Press.

The FAS Dean's Office announces new books to the FAS community and beyond. FAS faculty can inform us of their book’s publication through this webform.