The scholar of ancient Judaism uncovering forgotten aspects of Jerusalem’s past

Incoming FAS faculty member Sarit Kattan Gribetz studies life, religion, and community in one of the world’s oldest cities.

Every year, Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences hires dozens of exceptional scholars in academic departments across the sciences, humanities, and social sciences. This series profiles six of the faculty joining the FAS in the 2024—25 academic year, highlighting their academic achievements, research ambitions, and the teaching they hope to do at Yale. Learn more about the incoming ladder faculty and multi-year instructional faculty joining the FAS.

To Sarit Kattan Gribetz, a scholar of ancient Judaism and new member of Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Yale’s collection of libraries, art galleries, and museums is a dream come true.

“I plan to bring my students to the Beinecke to see medieval manuscripts and modern archival materials, to the Art Gallery to visit the numismatics collection, and the Divinity School Library to view early printed books,” she says, relishing the opportunity to help her students engage with so many primary sources in person. “I’ve already started working closely with Konstanze Kunst, the Jewish Studies librarian. I’m really excited to show students how hands-on, original research works.”

Kattan Gribetz joins the FAS as a tenured Associate Professor; she will teach in the Department of Religious Studies and the Program in Jewish Studies. She says that the rich variety of primary sources she studies, along with fantastic teachers during her days as an undergraduate, are the two major reasons she fell in love with her field.

“What I discovered in Religious Studies was a discipline that encompasses a broad range of sources: written, oral, ethnographic, archival, material, aural. Scholars of religion apply different modes of analysis to understand how traditions develop and communities form, and I found this approach to be a compelling way of studying the past and the present,” she recalls of her earliest classes in Religious Studies. “Really good teachers introduced me to that way of thinking about the world. As soon as I took my first course in the field, I realized that this is what I want to do.”

Now, Kattan Gribetz is steadily leaving her mark on the field by taking an outside-the-box approach to her scholarship. She draws upon a vast constellation of sources to uncover aspects of ancient Jewish life that might otherwise be taken for granted, like communities’ understanding of concepts such as time, gender, and rest.

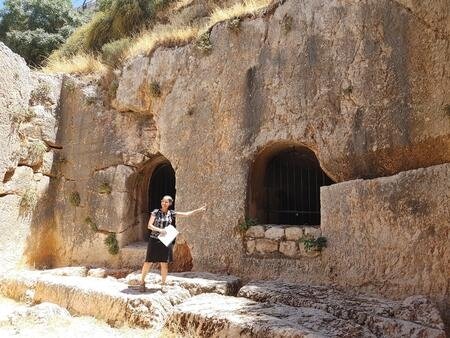

Her work involves both closely analyzing ancient rabbinic texts as well as traveling to archaeological sites and archives. “Now that I’m working on the history of Jerusalem, being in the city and getting a good sense of its many layers is indispensable,” she says of her visits to one of the world’s oldest cities. “It’s also great to meet the people of Jerusalem, because many parts of the city’s history are not found in textbooks or in published research, but in the memory of people who live there. They will take you to a particular stone or cistern or wall and tell you stories about them. I’m interested in how people and places transmit traditions across many generations.”

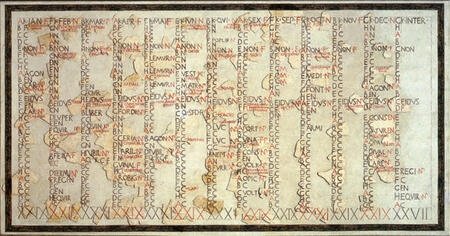

She published some of what she’s gleaned from early rabbinic texts in her book Time and Difference in Rabbinic Judaism (2020, Princeton University Press), which received a National Jewish Book Award. That book grew out of several simple yet powerful questions: “How did rabbinic communities organize their time? How did they think about their time, and how does studying the organization and conception of time help us understand both the rabbinic community and Jews in antiquity?” One chapter, for example, explores how the rabbis related to the Roman calendar and its annual festivals; another studies rabbinic stories that imagine God’s daily schedule and nightlife.

Upcoming projects continue to exemplify Kattan Gribetz’s dedication to finding innovative ways of looking at the ancient world. She’s still asking questions about time, particularly what nighttime meant for ancient rabbis, in a forthcoming article titled “Rabbis After Dark.” Another article will explore the idea of bein hashmashot (“between the suns”), which Kattan Gribetz says correlates more or less with twilight and is “a uniquely rabbinic time and idea.”

She’s also working on a project about the history of hours in antiquity with an international group of researchers from different disciplines to better understand where and when the twelve-hour division of the day developed, and how this form of timekeeping became ubiquitous.

All her work on time has made Kattan Gribetz wonder what else may be revealed by examining parts of history that haven’t yet been given their due, like the role of women in Jerusalem and ancient Judaism more broadly.

“My current work on Jerusalem has taken me to archives for the first time, and that has been a thrilling experience,” she says. She has spent time reading through documents at the Jerusalem Municipal Archives and viewing the personal papers of Jerusalem’s first British governor Ronald Storrs. Most recently, Kattan Gribetz visited the Special Collections at University College London to work on the Grace Aguilar papers. “Aguilar was a prolific English Jewish author who wrote a book titled Women of Israel, including several chapters about different biblical and Jewish women who lived in—and some of whom ruled— Jerusalem,” she recounts. “Physically holding her manuscripts was a moving experience.”

Those archival visits have helped shape Kattan Gribetz’s next two books, both under contract with Princeton University Press. The first, titled A Queen in Jerusalem: Helena of Adiabene through the Ages, will chart the legacy of a first-century northern Mesopotamian queen in and beyond Jerusalem, beginning from the very earliest mention of her by the first-century historian Josephus Flavius all the way to the street that currently bears her name.

The second will be a broader book about Jerusalem called Jerusalem: A Feminist History, in which Kattan Gribetz will focus on Jerusalem’s women and use a feminist historical lens to retell the history of the city. “With that book, I ask the question, how does our understanding of Jerusalem’s history change when we look at different sources and ask different questions about the city?”

“It’s both a book about Jerusalem and a book about the way that we tell history,” she says. “One of the first reactions that many people have when I tell them about this book is ‘oh, it must be a really short book.’ At first I might have agreed, but as I dig deeply, I realize that there is much more material than I could include in a single book. It’s far more shocking that these sources about women have been left out of previous histories than that they will be included in mine.”

Kattan Gribetz can’t wait to share her discoveries with students. She plans to teach both undergraduate and graduate courses on ancient Judaism and rabbinic literature, nighttime in antiquity, and the history and development of the Sabbath, or the seventh day of rest. She’ll also teach a first-year seminar on the history of Jerusalem. “I hope students will gain a deep and broad understanding of the ways in which Jerusalem is important religiously, politically, and culturally to the city’s diverse populations and to religious traditions and communities across the world.” She also hopes that students will feed their curiosity by digging deeply into the materials to ask and answer their own questions about the city.

Alongside her passion for the history of Jerusalem, Kattan Gribetz is eager to explore New Haven, too. “I’m looking forward to learning about Yale’s history and the history of the city,” she says, noting that her interest in time extends to cities’ architecture and design. “I’m always eager to see how different cities display their clocks and mark time, whether it’s the timetables at the railroad station or the bells that ring from the clock tower.”