Representations of Black Revolution and Victory in a Lost – and Found – Play

FAS faculty member Alex Gil discusses his new bilingual translation of a rediscovered earlier – and substantially different – version of Aimé Césaire’s ……And the Dogs Were Silent.

FAS faculty member Alex Gil discusses his new bilingual translation of a rediscovered earlier – and substantially different – version of Aimé Césaire’s ……And the Dogs Were Silent, based on the Haitian Revolution and the life of Toussaint Louverture.

Alex Gil understands what it’s like to find a treasure.

When he was a graduate student researching the work of the Martiniquais poet and statesman Aimé Césaire, Gil scanned a copy of a text labeled ……And the Dogs Were Silent, Césaire’s famous dramatic poem about an anonymous Black Rebel’s refusal to compromise his principles. Gil then discovered that the copy he’d scanned didn’t resemble the published version of And the Dogs Were Silent at all. In fact, he had discovered an early version of Césaire’s play that differed in almost every respect from the final version. No one was aware the earlier typescript existed.

Gil explained that this was “the kind of find in graduate school that makes you change your dissertation, which I did.”

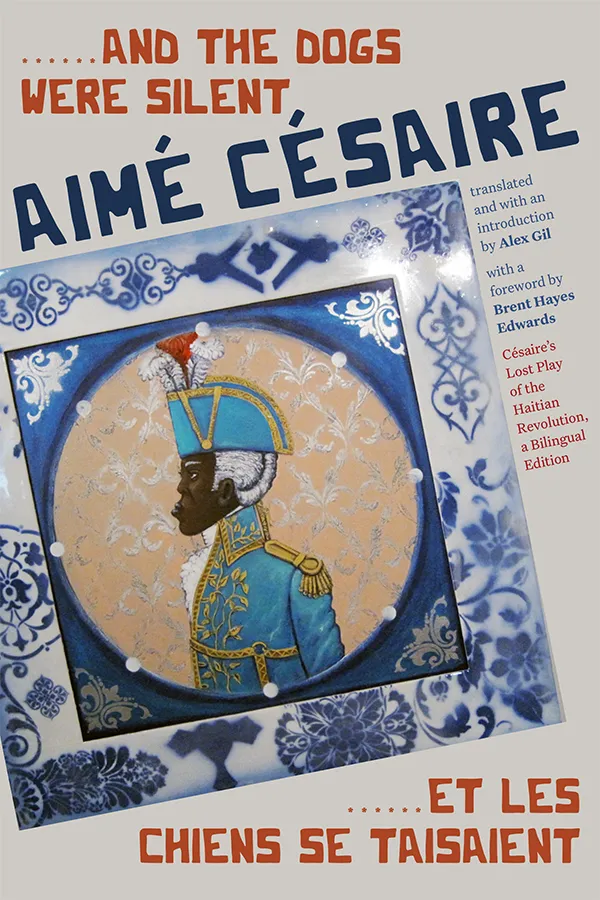

……And the Dogs Were Silent: Césaire’s Lost Play about the Haitian Revolution, a Bilingual Edition (Duke University Press) is a masterful French and English translation that invites readers to discover a different Césaire: one who passionately condemned colonialism and celebrated Black revolution and victory before he revised – and arguably softened – his play for a different audience.

Alex Gil, Senior Lecturer II and Associate Research Scholar in the FAS Department of Spanish and Portuguese, spoke with Natalie DeVaull-Robichaud of the FAS Dean’s Office about his experience discovering the typescript, Césaire’s reasons for changing the dramatic poem, and why this early version’s depiction of the Haitian Revolution is so relevant today.

Can we start by talking about the title? Why did Césaire choose the phrase “and the dogs were silent,” and why position it after six periods?

Gil: The question of the six periods is easy. Let me start there. In 1946, Césaire published the version of the work that everyone knows as part of his first collection of poetry, The miraculous weapons. That title didn’t have any periods. The typescript we prepared for Duke University Press, which is substantially different from the well-known version, had six dots, so we thought it would be a decent way of signaling that this is a different text even before you start reading it. Now the title itself is a bit of a mystery – or, better said, it’s up for interpretation. Some have suggested that it refers to the hounds that enslavers used to hunt down runaways. In that interpretation, their silence would suggest that, after a revolutionary victory, they no longer had prey. Césaire himself hinted at some point that it was connected to Anubis and ancient Egyptian myths of the afterlife. A recent suggestion by Césaire’s biographer, Kora Verón, connected the title to the local dogs, which apparently did not bark, that Columbus encountered on his first trip to Cuba. This last one intrigues me because Columbus provides one of the main foils of the play.

You were a graduate student when you found this previously unknown version of a play by Césaire. Can you describe that experience?

Gil: While doing research on his close associates, I found a footnote in the biography of his first translator into English, Yvan Goll, which mentioned that some Césaire manuscripts were housed at the municipal library in Saint-Dié des Vosges in France. I went to the small town hoping to find out a little bit more about the changes he was considering prior to publication for his most well-known poem, the “Cahier d’un retour au pays natal” (often translated as “Notebook on a Return to the Native Land”). Turned out that the proofs they had in the archive of that poem did not tell us much that we didn’t already know. While I was there, though, I scanned this other one to look at later. Three months later, I finally sat down to see what I had. I went back and forth between the published version from 1946 and the typescript with the dawning realization that I was reading something completely different. It was exciting. I’d found a treasure.

Instead of doing what most graduate students would do at that point – which is to hoard the secret and make sure nobody ever finds out until the dissertation comes out – I told everybody.

Why did you decide to share your discovery with the world right away?

Gil: Most of my professional life has been focused on digital humanities. I have always been a big advocate of taking over the means of production of our own knowledge and providing open access to that knowledge, if possible. At first, I started fooling around with doing a digital edition of the typescript; I put it online, but it didn’t receive that much attention. I never stopped thinking about the history of the manuscript, though, and how important it was to share a text that celebrates Black revolution and victory. His revisions reveal to us that Césaire transitioned away from speaking directly to popular audiences to a more arcane form of surrealist writing — going from an accessible language to one that is… not so much. My hope then and now, reversing the edits of the young Césaire, is that the original version would encourage a fruitful discussion about the representation of Black revolution and victory in the public sphere.

Why did you feel that now was the time for a bilingual translation that included the first English version of this play?

Gil: Years ago, I was invited to contribute to the French volume of the complete works. I prepared what is called a “diplomatic edition,” a form of transcription that preserves the deletions and additions and other strange typographical signs in print. These kinds of texts usually have a heavy scholarly apparatus. That volume was meant for a specialist audience in France. Once that was done, though, I was still interested in bringing it to an American and more general audience.

I wanted to bring this earlier version of the play to the attention of American scholars, or scholars around the world who read English, because I thought the text pointed to a lot of issues in the 2020s that we are wrestling with. I always thought that the text was somewhat unique in the history of Black revolutionary texts because it didn’t apologize for revolution. (I say, “somewhat unique,” because there are other examples.) We know from the history of the reception of the Haitian Revolution in the Americas that Black revolution was a taboo subject in English-speaking territories. For example, here in the United States, folks would get in trouble for talking about the Haitian Revolution before and even after the Civil War. We still don’t see a particular rush to tell stories in print or other media about the Revolution. Once film became the dominant medium for our societies, we see many attempts that don’t amount to much. To this day, we still haven’t seen a big Hollywood blockbuster about the Haitian Revolution because Black armies defeating white armies still makes audiences uncomfortable. I thought it was important to do this in English because of these reasons.

Césaire’s And the Dogs Were Silent was more surreal and symbolic than the typescript you discovered. Why do you think he eventually removed specific historical references from his play?

Gil: That is the question in everybody’s mind. Kora Verón, who I mentioned before, believes for example that Césaire was disappointed in Haiti in 1944 and thought it was a mistake to have that history be explicit in his play. Others believe that he is fully committing to surrealism by erasing the “subject matter.”

I’m not convinced that these hypotheses fully explain the erasures. I would call it a combination of several factors. The most important one is that the moment the Vichy Regime left Martinique, Free France finally started to feel real for Césaire. He starts to feel like there was going be an editorial center in Paris again. So, his audience goes from being a Black popular one in Martinique to an audience that is mostly white. And you can’t kill or call for the death of white people as bluntly as the play does if they are your audience.

There are a couple other things at play here as well. He’s having some problems in his marriage – his wife is having an affair. This becomes evident in the letters. At this point in time, he introduces the new character of The Lover, which can be found in the published version. In one memorable scene, the hero of this new version says “no” to The Lover’s advances because the mission of the revolution is too important, and he chooses not to let a romantic relationship determine his destiny. The drama became personal. He says as much in the letters.

How are Black revolution and victory represented in the typescript? Can you talk about the relevance of the representation of Black revolution for contemporary readers and scholars in North America?

Gil: I close my introduction with the work of Kellie Carter Jackson. Jackson’s first book, Force and Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence, is about Black abolitionists and the politics of violence. It was an attempt to recuperate a history of justified violence. Her second book is called We Refuse: A Forceful History of Black Resistance. Having Césaire’s text circulate in the same academic circles, maybe a little bit beyond, allows us to continue this important conversation about the justification of certain forms of violence in a way that we haven’t been able to historically.

Vaguely, we understand that fighting for freedom from slavery is justified, but from the Right wing, and maybe the center of this country, we still hear the message that the revolutionaries were savages, and Dessalines’ choice to exile planters or kill white militias was genocide. I think texts like ……And the Dogs were Silent could allow us then to be able to discuss how these histories unfolded in more nuanced ways. Questions of justified violence are still part of our life in 2024. We’re working it out as a society, and I think this text contributes to that conversation.

How do we speak of the justification of violence? We can go way back to Thucydides, for example, to find elaborate justifications for violence. But we need more recent examples where the justifications of violence are coming from the colonized, not just from the powerful, so we can have richer and more honest conversations. I’m talking about conversations in a mixed audience, because you don’t have to tell the Black folks who became free and formed their own country that what they did was justified — they know it was justified. They went from slavery to independence. Responsible conversations would add value to our own intellectual journeys and political destinies. In my opinion, artists and their work can allow us to have these conversations in serious and productive ways — hopefully without shutting down the conversation.

What would you like readers to take away from this bilingual edition?

Gil: I really hope readers leave the text fully convinced of the dignity of the Haitian struggle for freedom and the continued relevance of the Haitian Revolution for our dreams of equality and justice. If I could ask for a second, I would hope that readers also see how these struggles are connected to the way we use words, how we use language.

Alex Gil is Senior Lecturer II and Associate Research Scholar in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese in the FAS. His new bilingual edition, ……And the Dogs Were Silent: Césaire’s Lost Play about the Haitian Revolution, a Bilingual Edition is available from Duke University Press.

The FAS Dean's Office announces new books to the FAS community and beyond. FAS faculty can inform us of their book’s publication through this webform.