The Philosophy and Black Studies pioneer returning to Yale to foster a new generation of scholars

For Robert Gooding-Williams, returning to Yale as a professor represents not only a homecoming, but the opportunity to build an institutional legacy.

Every year, Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences hires dozens of exceptional scholars in academic departments across the sciences, humanities, and social sciences. This series profiles six of the faculty joining the FAS in the 2024—25 academic year, highlighting their academic achievements, research ambitions, and the teaching they hope to do at Yale. Learn more about the incoming ladder faculty and multi-year instructional faculty joining the FAS.

For philosopher Robert Gooding-Williams, returning to Yale as a professor represents not only a homecoming, but the opportunity to build an institutional legacy.

“There was a personal bias towards coming back to Yale,” says Gooding-Williams, who received a 2023 Wilbur Cross Medal from Yale’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Alumni Association to recognize his exceptional scholarship. “But I think there is also an opportunity to use Yale as a vehicle to strengthen the place of the work I do within the discipline as a whole.”

Gooding-Williams, who was an undergraduate (’75) and PhD (’82) student at Yale, joins the Department of Philosophy as Brooks and Suzanne Ragen Professor of Philosophy.

“I have always loved, both as an undergrad and as a graduate student, the intellectual intensity and interdisciplinarity of Yale,” he reflects, fondly recalling dinners spent intensely debating philosophy and political science with his fellow undergrads in the dining hall of Trumbull College. “This is a late career move for me, but given that I had a connection to Yale, given that Yale formed me intellectually more than any other institution with which I’ve been affiliated, it’s nice to be able to come back and to contribute to Yale’s institutional formation.”

Building institutional support for scholars working at the intersection of Philosophy and Black Studies will be a major focus for Gooding-Williams. He hopes to foster a community of thinkers working at the crossroads of these intellectual traditions. “Yale has an absolutely terrific Philosophy department. It also has a terrific African American Studies department, so one of the things I’m hoping to do is to create a combined PhD program for folks who want to do a joint PhD in Philosophy and African American Studies.”

That kind of combined PhD program didn’t exist when he attended Yale, but Gooding-Williams says the landscape of philosophy has shifted significantly since then. “Professional philosophy and philosophers have become much more open to work at the intersection of Philosophy and Black Studies, and to work focusing on figures in the history of African American political thought,” he says, pointing out that studying the intellectual contributions of people like Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. Du Bois, Alexander Crummell, Anna Julia Cooper, Alain Locke, and Frantz Fanon is now considered both interesting and worthwhile.

“I wouldn’t go so far as to say that what the late Charles Mills once called ‘the whiteness of philosophy’—in terms of not only who’s teaching philosophy, but what gets taught—is a thing of the past,” he explains. “But I would say that things are different. We’re at a point now where it’s important to continue to create sustained institutional space that supports and promotes that work, and I think that Yale has a great role to play.”

Gooding-Wiliams himself deserves considerable credit for this evolution in his field. After establishing himself as a formidable Nietzsche scholar with his book Zarathustra’s Dionysian Modernism (2001, Stanford University Press), he pivoted, beginning to carve out conceptual space for philosophical analyses of race and racism with his second book Look, A Negro!: Philosophical Essays on Race, Culture, and Politics (2005, Routledge). The essay collection examined the interplay of race and multiculturalism in the United States, and how race, class, gender, and sexuality interact to shape racial ideology.

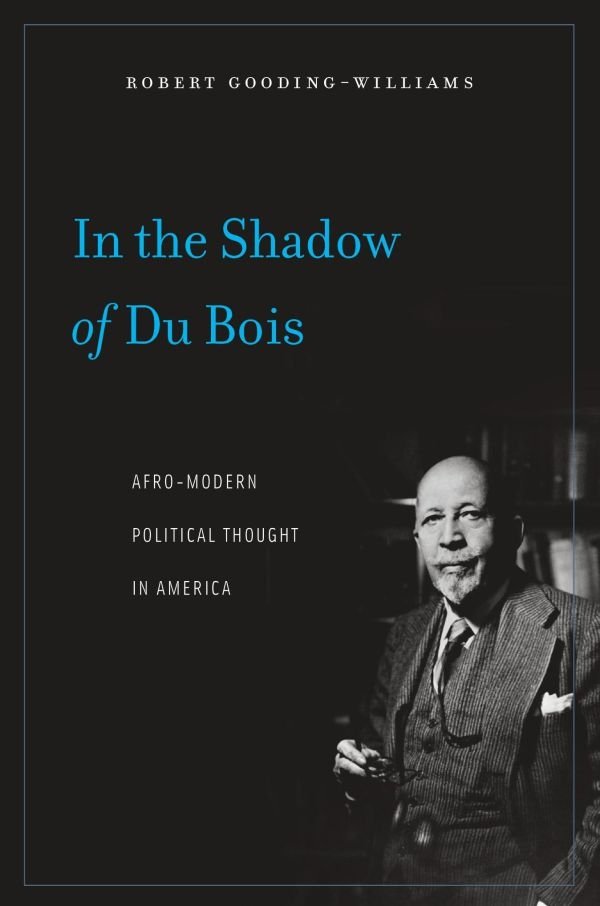

Gooding-Williams later published In the Shadow of Du Bois: Afro-Modern Political Thought in America (2009, Harvard University Press). The work won a Best Book Award in Race, Ethnicity, and Politics from a section of the American Political Science Association for its philosophical examination of Du Bois’s writings on a politics that could uplift Black people in the Jim Crow era. In that book, he brings Du Bois’s work into dialogue with Frederick Douglass’s My Bondage and My Freedom to critically examine how their ideas continue to influence debates about Black identity and leadership in America.

Gooding-Williams credits his own teachers at Yale with fanning his undergraduate interest in philosophy into the flame of a long, successful career. “I think the first time I read Du Bois in college was a course team-taught by a couple folks, including the philosopher Ben Ward, who had been a Yale Philosophy PhD student. There was also a junior faculty teacher named DW Crofts, and that was the first time I read Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction. That course was important to me because it was probably the one course I took that really exemplified the possibility of doing work at the intersection of Philosophy and Black Studies.”

There’s no shortage of inspiring teachers and colleagues Gooding-Williams remembers learning from at Yale: Sam Savage, Seyla Benhabib, Ruth Marcus, Ed Casey, and Karsten Harries—as well as George Schrader and Heinrich von Staden, his dissertation advisors—and his graduate peers Kathy Higgins, Larry Vogel, and Judith Butler.

Gooding-Williams plans to continue building upon the tradition his own teachers built, one he has continued through the years he spent at Simmons College, the University of Chicago, and his most recent position at Columbia. “In the spring semester I’m going to teach a graduate seminar called Political Philosophy and Race, and I’ll be bringing in lots of other philosophers who are doing work at the intersection of philosophy and Black Studies,” he says, looking ahead to the classroom with excitement.

In addition to that seminar, which he plans to offer every year to ensure ongoing conversations between Philosophy and African American Studies at Yale, he plans to teach a first-year seminar titled Philosophy, Race, and Racism and a seminar on Du Bois for grad students and advanced undergrads.

He also hopes to teach seminars on various figures like James Baldwin and Sylvia Wynter, and to contribute to the Department of Philosophy’s curriculum on 19th century German philosophy. “I expect that from time to time I’ll go back and teach a Nietzsche course. I haven’t given up the stuff that I originally worked on for twenty or more years.”

When it comes to his own intellectual exploration, Gooding-Williams’s fourth book will be published by Columbia University Press in the spring of 2025. That book is based on the Leonard Hastings Schoff Memorial Lectures he delivered at Columbia University, titled Democracy and Beauty: The Political Aesthetics of W.E.B. Du Bois. After that, he may start spending time with the works of Baldwin or Wynter, but any new writing would require “some years of reading and rereading and teaching.”

For now, he’s more excited about teaching students and turning Yale into a destination for future philosophers than immediately leaping into a new book project. “I love teaching undergraduates, especially in small settings,” he says with a smile. “Yale undergrads are fabulous.”