Marie-Helene Bertino’s New Novel Makes the Familiar Strange

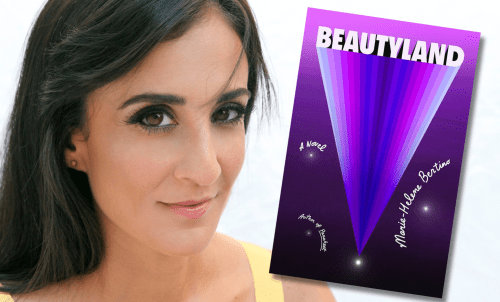

In a Q&A, Lecturer in English and Ritvo-Slifka Writer-in-Residence Marie-Helene Bertino discusses her new book, Beautyland, which explores an alien’s study of humanity.

In Marie-Helene Bertino’s lovely and tender new novel, Beautyland (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux), Adina is an alien who studies the world in all its beauty and absurdity – and in doing so, she connects with others who feel they don’t quite belong. Earth is a bewildering place for Adina, who is, as Bertino says, “more humane than most humans.”

Bertino, Lecturer in English and Ritvo-Slifka Writer-in-Residence in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, has an eye for the strangeness of daily life. She explains that Beautyland was inspired by notes she took on social norms which, upon reflection, may be rather odd, such as her grandmother’s tendency to rip her address from a magazine before giving it away. In the novel, Adina keeps similar notes that she faxes to her family – her “superiors” – in their distant galaxy so that they may better understand Earth. Shifting from funny to poignant, Beautyland shares Adina’s observations on growing up and living as both a human and extraterrestrial.

Bertino spoke with Natalie DeVaull-Robichaud of the FAS Dean’s Office about distance, differences, and what it means to have “a unique perspective on humanity.”

Throughout the novel, Adina and her superiors – whom she regards as distant family – correspond through a fax machine. How did you develop this unique approach?

Bertino: Developing the voice of Adina’s superiors required a bit of trial and error. What would be the most compelling—open enough to interpretation but also definitive? So far, I haven’t regretted erring on the side of brevity on the page. I had a great deal of fun writing their voice because it’s so different from mine. They are an example of something out there that she cannot see but believes in. They are also her family. My family comes from the French Basque region and Italy. Growing up, my grandparents would call and write letters to our relatives I’d never met. I was raised with the idea that family was a part of you that was very far away and only seen in photos and letters. I think this also went into the creation of Adina’s superiors.

The novel is divided into five parts, each named after the life cycle of a star, and each exploring a different stage of Adina’s own life. Can you talk a little about this structure?

Bertino: Figuring out the 5-part structure of Beautyland can be filed under what Zadie Smith calls, “middle-of-the-novel magical thinking,” though for me, it came towards the end of the writing process.

I checked every year Adina’s life contained a milestone (grade school humiliation, high school graduation, getting her first job) to see if there were any advancements in our understanding of the cosmos. Every time, there was a major one. It gave me shivers.

During most of the writing process I thought (and hoped) Beautyland would be an uninterrupted novel of vignettes. But I realized some of the vignettes were longer than others and I was forcing myself to write connective tissue vignettes that defeated the purpose of vignettes, which to me was to be associative, poetic, sky-facing. My students and I discuss how to let the project tell us what it needs its shape to be. I looked at the vignettes to see if there were any natural groupings—if any of them seemed to collect around certain subjects. I found 5 distinct eras in Adina’s life. Like I had for every other aspect in the novel, I looked up that number to see if it had any celestial significance and quickly found that the life cycle of a star is separated into five eras. It felt (forgive me) cosmic. The book’s structure (Adina’s life) is star-shaped. As Carl Sagan wrote, “We are made from star stuff.”

Throughout the novel, Adina shares delightful observations about the absurdity of our lives, such as our choice to eat the “loudest food” – popcorn – during movies. How can an alien’s perspective help us see our world?

Bertino: By making the familiar strange, I hope. And perhaps, vice versa. I’ve been lucky enough to be the recipient of some touching notes from readers who relate to Adina. Sometimes a newcomer can help us notice what we take for granted. Perhaps she is not so alien after all.

Adina is surprised that so many people empathize with her experience as an alien. What might this convey about feeling like an outsider? What can Adina teach us about experiencing the world a little differently?

Bertino: There are so many forced to society’s margins because of some element of difference. In isolation, it is easy to believe one’s feelings are extra to humanity. Adina is an extraterrestrial—extra to the terrain. This allows her a unique perspective to see just how fabricated, fragile, strange, tender, beautiful, and awful humanity can be. It’s not a coincidence that distance is also necessary for those of us in observing professions—journalists, reporters, writers, etc.

I had a professor in college named Father Lee, who said, “The more into the true self you go, the less like everyone else you look.” My theory is that proper attention paid to any human will reveal an idiosyncratic soul.

What do you hope readers take away from Beautyland?

Bertino: Into the lines of Beautyland I’ve secreted some real feeling and ideas about loss, love, joy, friendship, identity, and a certain frustration over the tendency some humans have to believe no other human can feel pain like they do. Maybe these ideas will help readers notice life on earth more acutely. And, since Beautyland is out of my hands and I now take my place as a reader of it just like anyone else, I hope it helps me do the same.

Marie-Helene Bertino is the Ritvo-Slifka Writer-in-Residence in the Department of English in FAS. Her book, Beautyland, is available from Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

The FAS Dean's Office announces new books to the FAS community and beyond. FAS faculty can inform us of their book’s publication through this webform.