Linked by Song and Sermon: FAS Professor Theorizes Afterliveness in the Digital Age

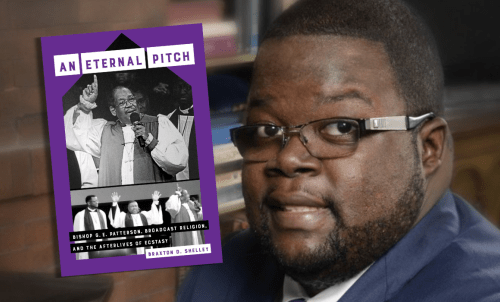

In his new book, Braxton Shelley, Associate Professor of Music, of Sacred Music, and of Divinity, explores Bishop G. E. Patterson’s eternal transmission of the sacred through Black Pentecostal music-making.

In his new book, Braxton Shelley, Associate Professor of Music, of Sacred Music, and of Divinity, explores Bishop G. E. Patterson’s eternal transmission of the sacred through Black Pentecostal music-making.

Like millions of people across denominations, Faculty of Arts and Sciences musicologist Braxton Shelley grew up listening to Bishop G. E. Patterson’s sermons on the radio.

For Patterson, the spiritual leader of the Church of God in Christ, broadcast technology was a useful metaphor for the transmission of scripture as well as a method to reach wide audiences.

Shelley recalls his fascination with Patterson’s musicality.

“He had this humongous voice – a big, meaty, bright, wide, vocal range. He was also an organist, so he understood not just the voice but the music.”

Shelley was in high school when Patterson died, but over the years, he noticed a peculiar phenomenon – Patterson’s recorded sermons continued to reach new audiences through digital platforms.

“I became fascinated by the degree to which Patterson seemed to not die – living on in a TV broadcast, living on in various digital platforms – and An Eternal Pitch was trying to figure out why Patterson was being disallowed death and how that disallowance – that ongoingness – related to the kind of musical structure of his sermons.”

Shelley’s new book, An Eternal Pitch: Bishop G. E. Patterson, Broadcast Religion, and the Afterlives of Ecstasy (University of California Press), is a biography of Patterson, a history of broadcast religion and Black Pentecostal music, and what Shelley terms a “musicological media archeology.”

In a recent conversation with Natalie DeVaull-Robichaud of the FAS Dean’s Office, Shelley discussed Patterson’s “afterliveness,” the ways Patterson theorized instrumentality, and the profound impact of Black culture on media over time.

What led you to approach Bishop Patterson through Black Pentecostal music?

Shelley: A lot of people could have written about Patterson – politicians, theologians, folks in religious studies, folks in media studies – so the idea that I, as a musicologist, would go after Patterson is somewhat surprising. I mean, I have training in those other fields, too, and I’m a faculty member at the Divinity School, the Institute of Sacred Music, and in the FAS Department of Music. But I argue in the book that to understand Patterson is to listen to the sonic details and the choices he makes with how he says the word, how he sings the word – when, where and how he chooses to use music relates to his theology, to the message he’s trying to get across and what his audiences are hearing both during his life and after his death. I feel lucky, frankly, to get to theorize afterliveness.

How did Patterson develop his distinctive version of broadcast religion?

Shelley: When the Church of God in Christ came into institutional formation, it was the oldest Pentecostal Church in North America. There is a rich legacy that G. E. Patterson stepped into that included musicality, [and] that legacy included the use of prayer, cloths and oil. The idea that God is so real that God’s presence can be felt and disseminated through and found in made objects is the kind of basic devotional materiality that is the condition of possibility for broadcast religion. At the same time, the music industry discovered that all these new Black people who came to urban centers [through] the Great Migration left farms and now have jobs. There’s a Black mass market for religious-oriented products, for recorded sermons, for gospel music. Religion becomes something to be mass mediated, to be mass consumed. And so Patterson grew up in that milieu.

My argument is that Patterson himself was trying to be the right kind of receiver. You can hear in his preaching’s musicality [as he tried] to tune his body to the right frequency at which he can pick up an eternal transmission of sacred myth. He was fascinated by the possibility of mass communications of broadcasting, and you could see that later in his life. He’d use satellite and other technological implements as metaphors to deliver a theological point. He believed that spiritual power could flow through microphones, through cameras, through recordings just as well as it could flow through him in an in-person event, and through a prayer cloth, through oil. The word is always waiting to be made flesh, always waiting to be materialized and can take place if you use the right kind of receiver.

How can music create connections with other times?

Shelley: The event of a song or sermon is a discreet happening, but that duration is also connected to every other time I sang that song on every other day in the calendar and every other time anybody else ever sang the same song. Just that one little piece of music – three, four, five minutes in duration – cuts across all these other kinds of temporality to link people or to link experiences in different places in time. Recording is about making available not so much copies but versions of a single experience. I was thinking about games, [which] are contrived. They have rules you must submit to in order to play them. [Similarly,] to take part in a song, you have to get in the key. The song is in tempo and has meter, and there are no two ways to be in a song. If there are thousands of us or two of us, we have to synchronize ourselves and abdicate some of our agency. That moment of unification in a single spatial, temporal intersection in one congregation at one church on one Sunday morning holds within it the power to link that congregation to every other place. When you add to it the text, you are singing about something that allegedly took place on an ancient battlefield thousands of years ago. Now there’s a sonic portal that opens between the world of the scriptural text or the world of the original recording or the world in which Patterson had preached a sermon in 2001 that I get to watch in 2024. We are linked by the song, by the sermon, by the musical, temporal sonic unfolding – genuine connection. And that’s how I approach it.

How does Black Pentecostal music facilitate “afterliveness”?

Shelley: Black digital culture, in good ways and through appropriation and commodification, is the lifeblood of digital culture. The eternality of the Word and religious beliefs about afterlife are laced into the technological affordances that recording has made available for more than a century, but the digital system intensifies them. This Black Pentecostal phenomenon is a powerful [place] from which to watch digital culture unfold and to see [in an] archaeological sense that what Patterson was up to in his life comes into fullest fruition after his death. It might have been hard for somebody born 1939 to imagine digital [spaces], but at the same time, Patterson was always repeating these little fragments across his sermons almost as if he was trying to do a reel. It’s because what technology facilitates changes our communicative and expressive desires. They endure. In the Black Pentecostal context of afterliveness, you get to really see the sort of collision of the old or the hyper-old and the hyper-new right now – ain’t nothing older than the idea that death is not the end and that the Word is eternal, and there’s nothing newer than TikTok. But you get to see that collision and that productive tension unfolding with Black theorists who are grappling with what it means for Patterson to be both dead and alive and for digital platforms to be both evil and life-giving.

What can we learn about theorizing media and instrumentality?

Shelley: Bishop Patterson was a media theorist. He was actively engaged in figuring out what media are, what media can do, what media are for. I want people to attend to Black cultural practices as sites of theorizing. What is a song? What is voice? You don’t have to write a 300-page treatise about it to theorize it. I think Aretha Franklin is theorizing ecstasy when she co-mingles spiritual and sexual connotations in her performance. She’s making an argument about what ecstasy is. Patterson is certainly theorizing what media are for when he joins his voice, designed in a particular way to suit traditional communications media. He’s theorizing what somebody like Twinkie Clark is theorizing: instrumentality. What is an instrument when, while playing an organ solo, Clark interjects her voice? She makes her voice sound like an organ, and the organ sounds like her voice. Black sound, Black music, and making Black expressive culture are theoretical endeavors.

Braxton D. Shelley is Associate Professor of Music, of Sacred Music, and of Divinity. His book, An Eternal Pitch: Bishop G. E. Patterson, Broadcast Religion, and the Afterlives of Ecstasy, is available from University of California Press.

The FAS Dean's Office announces new books to the FAS community and beyond. FAS faculty can inform us of their book’s publication through this webform.