The Holy Alliance: Isaac Nakhimovsky on the history of liberalism and federal politics

Nakhimovsky, Associate Professor of History and Humanities, discusses the surprising history of a nineteenth-century political project.

Isaac Nakhimovsky, Associate Professor of History and Humanities in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences, has a sleepless newborn to thank for the inspiration that culminated in his latest book, The Holy Alliance: Liberalism and the Politics of Federation (Princeton University Press, 2024).

Nakhimovsky found himself reading Tolstoy’s novel War and Peace in the middle of the night when a character in the novel’s opening scenes caught his attention. That character was based on an Italian politician, Scipione Piattoli, and Nakhimovsky became interested in Piattoli’s connections with his student, the Polish revolutionary Adam Jerzy Czartoryski. Both men turned out to be important for understanding the origins of the Holy Alliance, an 1815 treaty announced by Tsar Alexander I of Russia designed to help end “destructive rivalries among European states and empires” in the wake of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars.

“When I started writing, in some ways this was a post-2016 book; this was me thinking about the aftermath of Brexit,” said Nakhimovsky of his decision to focus on another tumultuous moment in Europe’s history. “It was a time when assumptions about continuities in history and politics seemed increasingly doubtful, so I was interested in the question: how did people in the past make sense of a moment of uncertainty about systemic change?”

Nakhimovsky wanted to dig into the language, imagery, and ideas people used to make sense of the potential encapsulated in the Holy Alliance—a “political intervention” that started off as an “idea of progress,” he writes, but later became a label for reaction.

While the Holy Alliance may seem distant from our current political landscape, Nakhimovsky realized that it “gave rise to both the expectation of progress and the experience of reaction” in liberal politics. “The persistence of the problems it was supposed to address is a prompt to reconsider the expectations and experiences attached to many other ‘new holy alliances’—past and present.”

Nakhimovsky spoke with Michaela Herrmann of the FAS Dean’s Office about what’s missing from textbook descriptions of the Holy Alliance, why he decided to trace the history of failed revolutionaries, and what lessons from this era might apply to our contemporary discussions about liberalism.

Why did you want to write a book about the Holy Alliance?

Isaac Nakhimovsky: The standard stories are either that the Holy Alliance was just an expression of the Tsar’s personal religious mysticism, or that it was a conspiracy defending the status quo against progress. The second of these is still familiar in political cultures shaped by the Communist Manifesto of 1848, which famously mentions the Holy Alliance in its second sentence. But the identification of the Holy Alliance as an emancipatory project with real content has almost entirely disappeared, even though people can still understand in hindsight why contemporary observers might have experienced the French Revolution, for example, as the dawn of a new era. So why did similar people, or in some cases the very same people, with the same ideas, think the Holy Alliance was one too?

I wanted to explain why the Holy Alliance, despite its outcome, was initially greeted with such enthusiasm by a wide range of early liberals. What were their reasons for seeing it as a solution to the political, legal, financial, economic, and demographic problems of European states and empires? Why was it even seen, from abolitionist New England to revolutionary Haiti, as pointing the way to a new Atlantic world without slavery or war? The answers have to do with the fact that the Holy Alliance was originally an Enlightenment idea invented in Paris and London before it was projected eastward onto Russia. It was recognizable as an expression of the constitutional and economic ideas of the 1780s as well as a performance of Enlightenment politics in how it appealed to international public opinion.

It's interesting to realize that a lot of people who you would typically trust on the topic of liberalism also thought that the Holy Alliance was a good idea and could be a liberal and emancipatory project.

Nakhimovsky: Yes, people you can’t easily dismiss because they still figure in canonical histories of liberalism, even though such histories no longer include the Holy Alliance. But it's important to make clear this is not the kind of book that tries to say, “well, actually the Holy Alliance was a good thing” or anything like that. It's trying to say that the reasons why liberals invested their hopes in the Holy Alliance were the same reasons why liberals invested their hopes in contemporary projects to reform the British Empire, or in the federal constitution of the United States of America, or in the vision of a federation of newly independent Spanish American republics. The Holy Alliance was the European counterpart to these other great federal projects of the early nineteenth century, an attempt to create something like a United States of Europe, complete with an expanding frontier to the east.

This comparison is not my invention but one that was deployed at the time by some of the historical characters in my book. I think that this opens up a new comparative perspective for thinking critically about how expectations and experiences of liberal politics can diverge. It’s a comparative perspective that extends forward chronologically as well, because the Holy Alliance was a historical experience that people kept referring back to during the 20th century and through the Cold War. And I think the history of the Holy Alliance, examined systematically, still matters for thinking critically about federative politics and its emancipatory as well as reactionary potential.

Can you tell me about the process of researching and preparing to write this book?

Nakhimovsky: This book took a long time to research and write because it had multiple starting points and part of the process was figuring out how they were connected historically as well as conceptually. There were people like Czartoryski and Piattoli, who were immersed in Enlightenment discussions of perpetual peace, or what it would look like to resolve the problem of destructive competition among European states and empires. They revealed how these discussions were projected eastward onto Poland and Russia and forward into the Napoleonic period. And then there was the convergence with Atlantic abolitionism, and finally the fact that the very first history of liberalism, which was published by a German philosophy professor in 1823, concluded by proclaiming the Holy Alliance “the most liberal of all ideas.”

Mostly my process was to work outward by tracing contemporary responses to the Holy Alliance and trying to explain their reasons for the judgments they expressed. Some of my central characters turned out to be failed revolutionaries from smaller countries like Switzerland or Poland, who were trying to liberate their countries. Generally, what people do when their wars of national liberation fail is look for outside help, and these people were plugged into these amazing transnational, transatlantic networks. So they enlisted these networks to try and save their own countries, and along the way, maybe that would require using Russian power to transform Europe and maybe even the whole Atlantic economy. The Holy Alliance turned out to be a version of this kind of strategy.

Czartoryski is a good example. As a young man in the 1780s, he went to Paris and London and connected with some of the most important political and intellectual figures of the time. These were connections that Czartoryski later reactivated when he was close to the Tsar and working to turn Russian power into an instrument for transforming Europe. Even though Czartoryski condemned what the Holy Alliance became, he still insisted that it was a failed version of the kind of politics he had encountered in 1780s Paris and London. By the end of the 1820s, most of his fellow liberals saw the Holy Alliance as a reactionary conspiracy against national sovereignty; but Czartoryski still insisted that it was a federative project gone wrong, and that there was still no viable alternative to that kind of 1780s politics.

The first chapter of the book explores "contemporary visual representations of the Holy Alliance." Can you talk about one of your favorite images, and what they tell us about contemporary public perception of the Holy Alliance?

Nakhimovsky: When you dig into these images, they're complicated; they're so intricate and historically specific that sweeping judgments like, “oh, this is just religious mysticism,” or, “this is a reactionary conspiracy” become impossible to sustain. Clearing away those retrospective characterizations is a prerequisite for explaining the actual reasons why contemporaries saw the Holy Alliance differently.

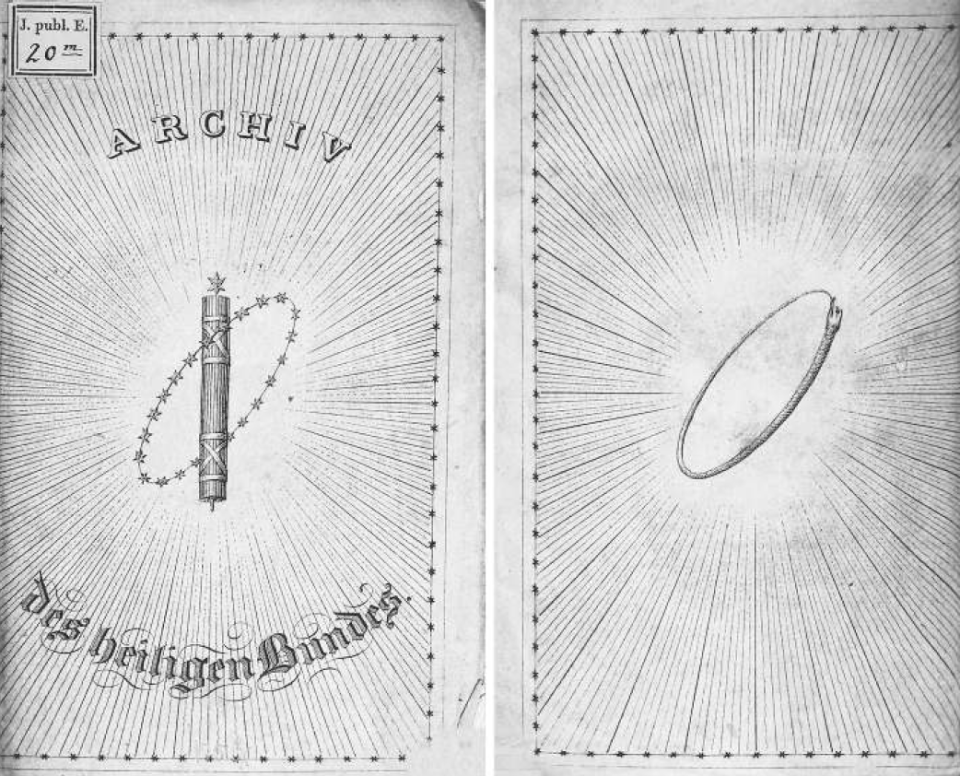

One striking image is the cover of the Archiv des Heiligen Bundes (Archive of The Holy Alliance), an 1818 publication which became one of my most important discoveries and sources. It's a compendium put together by a librarian in Munich [who thought], “This is a world historical event. We need to compile sources that document how contemporaries are making sense of this, both so that we can form a good judgment of this ongoing world historical transformation and for the use of future historians.”

The image on the cover is striking because it's completely impersonal—unlike some other contemporary images it's not focused on the personalities of the Tsar and other leaders. It shows an emblem with the Roman symbol of authority, the fasces, surrounded by a familiar circle of stars, reminding you of the European Union’s flag, glowing in divine light.

The unfamiliar idea of the Holy Alliance as ‘the most liberal of all ideas’ goes closely with this image. If the center of the image is the instruments of force being given legal authority—and that's what the state is, it authorizes and legalizes force—then here the state and the law are being given new spiritual significance: they are being elevated and turned into an ethical community based in universal values.

What can contemporary observers of politics learn from this new analysis of the Holy Alliance? Is there anything in particular you hope readers take away from the book?

Nakhimovsky: One takeaway is that the Enlightenment produced an analytical framework for understanding federative politics which was brought to bear on the Holy Alliance by Czartoryski and others, and I think it retains significant explanatory power. From this perspective, federative politics depends on the intentions, coherence, and capacity of the agent legislating the federal constitution or treaty system and serving as its “guarantor.” This is the agent taking individual responsibility for maintaining the collective security and prosperity of autonomous members, whether that is an alliance, a superpower, or some other kind of agent.

In the case of the Holy Alliance, liberal expectations were grounded in Enlightenment ideas about how Russia could help solve Europe’s problems from the outside, ideas that involved expectations of how Western investment in and migration to the Russian Empire would shape Russia’s development, and how networks of Western opinion could help guide the Tsar’s interventions in Europe in ways that would help redirect the destructive behaviors of European states and empires. This is a perspective that I think prompts us to think again about, say, the fates of 20th century international systems.

More generally, though, I hope that this book illustrates why it’s important not to start with an -ism, like liberalism, and investigate a history on that basis. If you begin in that way, then you’ve really constricted not only what you can see in the past, but also what you can see in terms of present and future possibilities.

In the end, the book’s conclusion is that it’s an open question whether the hopes invested in current federal systems will seem any less implausible to future generations than liberal expectations of the Holy Alliance do today. But at the same time, it would be precipitous to conclude from a particular crisis of a particular federal system that the politics of federation is always and everywhere unworkable. That's the two-sided message that the book ultimately arrives at.

Isaac Nakhimovsky is Associate Professor of History and Humanities in the FAS. His new book, The Holy Alliance: Liberalism and the Politics of Federation, is available from Princeton University Press.

The FAS Dean's Office announces new books to the FAS community and beyond. FAS faculty can inform us of their book’s publication through this webform.