Art Historian Marisa Bass on Monuments, Myths, and Modern Republics

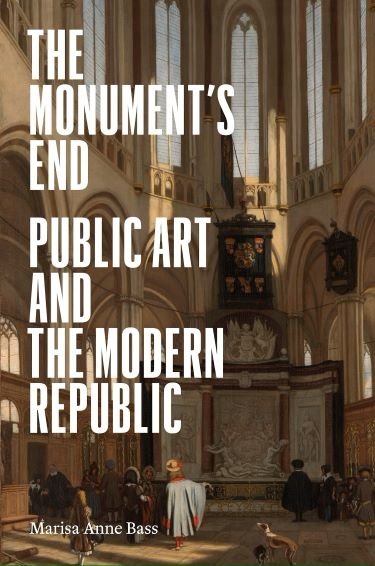

Marisa Bass, Professor of History of Art, discusses her new book, The Monument's End: Public Art and the Modern Republic.

When you picture a monument, what do you see? So many public monuments look the same: a man on horseback, a man atop a pedestal. It’s no wonder that they often meet with collective indifference.

For Marisa Bass, the tension between that indifference and the outrage that monuments have inspired in recent years offered a fascinating starting point for exploring the art history of political representation in her new book, The Monument’s End: Public Art and the Modern Republic (Princeton University Press).

“Monuments generate myths and present them as history,” said Bass, Professor of History of Art in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences. “In every case, they make a claim for a certain version of history that includes some and excludes others.”

Monuments became a major topic of public discussion following the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia on August 12, 2017. Public outcry led to the toppling or removal of monuments in the United States and around the world.

The changing landscape of contemporary monuments informed Bass’s study of their longer history – specifically in the early 17th century Dutch republic.

Bass spoke with Michaela Herrmann of the FAS Dean’s Office ahead of the publication of The Monument’s End, and highlighted the history of response to monuments, their fraught role in republics, and why monuments get removed or destroyed.

I love the book’s opening line: “monuments have always been a problem.” You write about how people retain their drive to make monuments, even though they often end up getting torn down. What brought you to study and write about monuments?

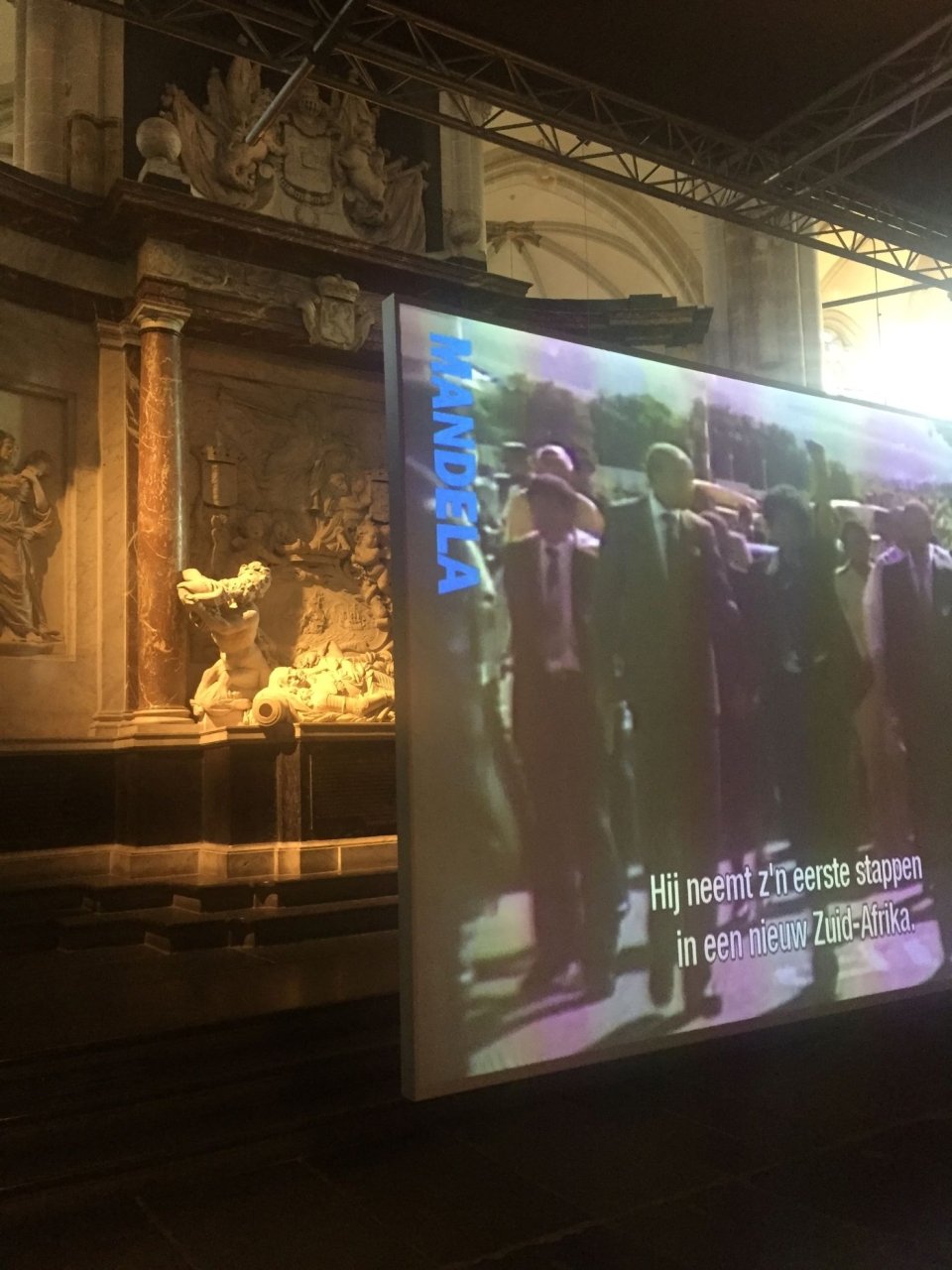

Marisa Bass: The book really started during the years I lived in Amsterdam. Many of the churches in the Netherlands have been turned into almost secular museum spaces. One in particular—the New Church (Nieuwe Kerk) in Amsterdam, which is right in the center of the city—regularly hosts exhibitions.

I would go to these exhibitions, and I started to notice that there was a monument in the middle of the church that in almost every case, was obscured by the temporary display; a screen was placed in front of it, or a large painting. And so I started to wonder, “What are they hiding?”

It's a tomb monument dedicated to Michiel de Ruyter, who was a Dutch admiral in the 17th century – the most famous Dutch admiral. He was venerated as a national hero, at least until very recently, when his involvement in the Dutch slave trade and the rise of the Dutch Republic’s commercial empire in the 17th century has started to receive more attention. But there was almost nothing written about the monument itself.

According to the traditional account, the 17th-century tombs of Dutch admirals like de Ruyter were meant to represent the demotic spirit of the Dutch Republic, but this tomb was so clearly about dominance and global power. I started to think it would be interesting to write a book about Dutch art focused on monuments rather than paintings, since painting is the medium through which Dutch art is still almost always understood. And I also started to think about the particular problems that monuments raise in the context of republics.

After the Unite the Right rally, the latter question really came to the fore for me. How could I write a book about Dutch art that would be both historical and resonant in the present? What did it mean to be an American writing about a Dutch political tradition, and how could I use that to say something that might not be said otherwise? I should mention that I grew up in Charlottesville and my dumbfoundment over the tacit acceptance of Confederate monuments around me was one of the reasons I became an art historian.

You mention in the introduction that many monuments are not necessarily art. Can you talk a bit more about that, the difference between art and a monument?

Bass: In art history there has been surprisingly little scholarship about monuments, perhaps on the assumption that most of them don't count as art. If we take “a work of art” to be a work that is inventive and, in some sense, the product of an original thought, then many monuments would not make the cut.

But all monuments, even the most boring among them, have aesthetic qualities. Even the most generic Confederate monument has an aesthetic quality. The repetition of a familiar form and type, like a man on horseback, is an aesthetic choice—a choice that I describe in the book as uninspired by design.

There are also monuments in my book that are highly problematic in terms of what they represent, but that could easily be put into the traditional category of “art” because they were made by artists with great skill, or because a lot of thought went into their design. Basically, I’m not interested in saying what is or isn’t art but in the slipperiness of the category and how monuments fit into it.

I talk a lot in the book about how the history of monuments is really a history of war. That is not only because so many monuments were made in the context or aftermath of war, but because they are also weapons. I was fascinated, for instance, by the decision to melt down the statue of Robert E. Lee from Charlottesville. There are so many monuments across history that have been made from melted down weapons, particularly cannons. Or monuments have been melted down and turned into weapons, which is a really extreme example of how closely they are connected.

You wrote this book between 2016 and 2023, when monuments and their removals were a big part of the public conversation. Did that wave of discussion present any challenges or impact the theory or process of writing the book?

Bass: I knew, even before the contestation of monuments in the United States and around the world over the past several years, that I was not interested in writing a book that explored the question of what a monument is. I was much more interested in what monuments do and what they fail to do. My book is really about a history of iconoclasm; it’s as much about art as about its destruction or the antagonism that it inspires. The taking down of monuments, as well as the conversations about what to do with them afterward, were very generative to me.

I wasn't explicitly writing about that recent history, but it made me think about how the media coverage of that whole debate was very centered on questions like, “should these monuments removed from public spaces go in museums? What should we do with them now?” As opposed to the questions of, “why do we have them in the first place? What were people asking these monuments to do when they were made?” There wasn’t a discussion about how the problem is not just what monuments represent, but how they represent and the effects that these representations have on audiences.

If anything, the challenge was maintaining my historical focus while also trying to think in relationship to those questions. It would have been very easy to just start writing about what's happening now, but as a historian, I wanted to write a book that recovered something that happened in the past. I also wanted to be transparent about the fact that history is always written in relationship to the present, whenever it’s written.

You write that one “purpose” of monuments is that they can act as a “stage for people to perform their connections with the past.” You specifically discuss a painting of a monument in the Netherlands. Can you talk about that monument and how it relates to this concept of performing our history?

Bass: The monument I write about in the introduction is probably the most famous of the funerary monuments in the Dutch Republic because it was made for the person known as the “father of the Fatherland,” William of Orange. I decided that rather than writing about that monument directly, I would write about a response to the monument in a painting. It’s a painting, I argue, that conveys skepticism about whether this monument was the right way to represent a major historical figure who's associated with the founding of the republic.

In the painting, we see this well-to-do family posing next to the monument who clearly think of themselves in connection with it—they are part of this republican project that's being established in the Dutch Republic. But the painting itself is actually quite ambivalent about the monument being a good representation of that political project. It's very self-conscious. It's basically a form of art criticism.

What do you see in the painting that indicates ambivalence?

Bass: The monument is not represented in the space it actually occupies in the New Church (Nieuwe Kerk) in Delft, where this monument is still located today. The stone is also represented differently: it's represented with exclusively black reflective marble, which was very popular in funerary sculpture at the time. But in reality, the monument uses both white and black marble. So it's not accurately represented, and anyone who saw this painting in the 17th century would have known that.

The monument is also turned in a way so that you don't actually see the embodied representation of William of Orange that's on the front. That choice de-emphasizes the glorification of the individual that is in so many ways the crux of the classical monument: the statue of the emperor, the person on horseback.

In general, I think there's a lot of interest in 17th-century Dutch art about the questions of what a public is, what a public looks like, and what a public is allowed to do – because the very idea of a republic is founded on the notion of representing a public. But certainly in the Dutch Republic, as in so many republics since, the people who were actually considered to have full citizenship and a voice were a very small portion of the overall population.

The desire to remove monuments might have seemed very jarring in the last few years, but your book demonstrates that removal is often a normal part of a monument’s lifespan. Can you talk about the desire to remove monuments going hand-in-hand with the building of monuments?

Bass: Absolutely. You can certainly find the destruction and mutilation of monuments for as long as monuments have been made. There's even a special term for it if you're talking about antiquity, which is damnatio memoriae: to damn someone in memory. That often involves simply chopping the face off a statue, and sometimes re-carving it with a different ruler's face.

My book begins with the most infamous statue ever made in the history of the Netherlands. It was infamous because it was made and erected in the Netherlands by an enemy to the Netherlands—a Spanish general who had been sent by the king of Spain to curb the rebellion in the Netherlands against Spanish imperial rule.

I identify the history of that statue as central to the ways that the Dutch were inspired to experiment with what a monument is. They had this glaring case of why monuments do not work, and why you do not put a statue of yourself on a pedestal in a public place. But what's the alternative? We're still grappling with that question. In the wake of the Unite the Right rally, in the wake of all the discourse about monuments, there is no answer. What's the better version of a monument? Monuments have a long, messy history, and that's why I say that the book is not about defining what a monument is, but asking, what are we doing with them? What have we always been doing with them?

In the afterword, you write about a monument to Lewis and Clark in your hometown of Charlottesville. Why did you close the book with that example?

Bass: In the afterword I really tried to bring the book up to the present and think about where we are at, at the time of my writing, with the larger questions that I explore in a historical context within the book. I could have chosen so many monuments to put in the afterword. I ultimately decided to use the first monument I ever remember noticing. When it still stood in the center of Charlottesville, it was so prominent. Anybody you asked who lived in Charlottesville would have known where it was. I don't think that was true of Robert E. Lee monument prior to the protests against it.

The monument commemorates the westward expedition of Lewis and Clark, but it also includes a crouching representation of Sacajawea at their feet that is both the most “original” and most problematic part of its design. It is a monument connected to the history of Native American genocide and the violent seizure of Native American land. But because the conversation in the national media was focused on monuments connected to the history of slavery, White supremacy, and anti-Blackness, it didn't receive the same attention even though it has all the same problems. So I thought that this was my chance to contribute to the historical discourse moving forward about what has happened in Charlottesville. That monument shouldn't be written out of the history of what transpired there.

The Lewis and Clark monument is also significant because it’s the only one of the monuments critiqued at that time that is still standing in Charlottesville today. It's now in a parking lot in Charlottesville’s Darden Towe Park, not at the center of town, but a park is a public space, and its pedestal is still in its original location. To me, that’s a powerful example of how we are still trying to figure out what do with monuments.

Marisa Bass is Professor of the History of Art in the FAS. Her book, The Monument’s End: Public Art and the Modern Republic, is available through Princeton University Press.

The FAS Dean's Office announces new books to the FAS community and beyond. FAS faculty can inform us of their book’s publication through this webform.