Exploring Blackness in the Works of Miguel de Cervantes

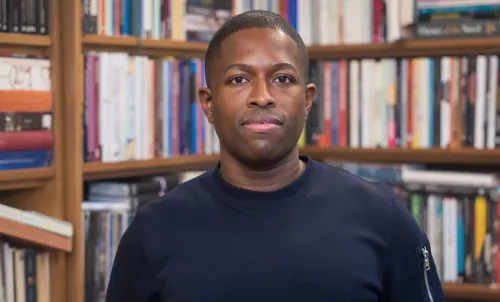

Nicholas R. Jones talks about his upcoming book Cervantine Blackness, charting new methodological terrain, and challenging longstanding interpretations of black characters in Miguel de Cervantes’s works.

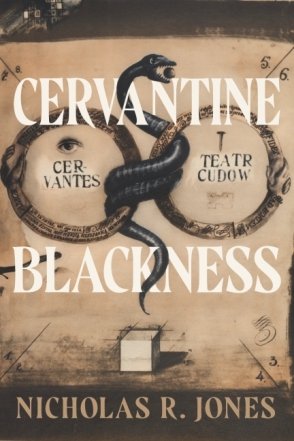

Nicholas R. Jones, Assistant Professor in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, talks about his upcoming book Cervantine Blackness (Pennsylvania State University Press), charting new methodological terrain, and challenging longstanding interpretations of black characters in Miguel de Cervantes’s works.

Nicholas R. Jones had a lot to get off his chest.

“Writing this book was very liberating,” Jones said of Cervantine Blackness (November 2024, Pennsylvania State University Press). His upcoming book plays with the genre and form of academic writing to explore the culture, joy, despair, and other rich experiences of black culture and black life in the works of 17th-century Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes.

Jones’s first book, Staging Habla de Negros: Radical Performances of the African Diaspora in Early Modern Spain (2019, Pennsylvania State University Press), spurred both pushback and transformation in his field of early modern Iberian studies. Its publication was swiftly followed by the COVID-19 pandemic and worldwide protests against police violence, particularly in the wake of the murder of George Floyd.

Cervantine Blackness began to take shape against the backdrop of these world-changing events—including a protest in San Francisco that ended with the defacement of a Cervantes statue and subsequent global outcry. As Jones and a colleague wrote an op-ed for a Spanish news outlet about the protest, he realized that his thoughts on society’s political turmoil and his frustrations with early modern studies scholars’ thinking about blackness and agency could add up to a special, singular piece of writing.

“I see this book as an experiment in being vulnerable and blending expectations,” Jones said of his newest work. “The form reiterates the idea and the evidence that the writing of black critics and black intellectuals is serious and demanding work.”

Jones spoke to Michaela Herrmann of the FAS Dean’s Office about the concept of Cervantine blackness, the analytical lens it adds to early modern studies, and why it’s so important to continue to challenge scholars of early modernity to deepen their understanding of black literary characters.

What led you to write this book?

Nicholas R. Jones: To be honest, a lot. Frustration. There was a lot that I needed and wanted to get off of my chest, especially thinking about the short, quick reception and aftermath of my first book, Staging Habla de Negros, which really transformed and exploded in early modern Iberian studies how to talk about, write about, and analyze—in a very traditional way—black literary characters. Before that book came out in 2019, the standard unquestioned reading and interpretation of racialized blackness was that these black literary characters are caricatures or buffoons, that we have to talk about their racialized blackness in terms of stereotypes, so on and so forth. My first book reads against and transforms that narrative.

I didn’t expect the first book to have the impact that it did. I didn’t expect it to touch and transform my immediate scholarly home in really impactful and positive ways. But on the other hand, there have been and continue to be problematic appropriations and co-opting of my work, in terms of the lack of citations and the lack of critical and rigorous engagement with what Staging Habla de Negros did, and what it continues to do.

I would say the second element and genesis of Cervantine Blackness has very much to do with politics, different disenfranchised and marginalized publics, and me reacting to and responding publicly about a whole slew of societal injustices. I would say a lot of that exploded and came to a head, so to speak, in 2020. This was during the pandemic, obviously, but also in 2020, in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park there was a public protest including the “defacing” of the Cervantes bust monument. A good colleague and friend of mine were talking about that particular public protest and reacting to it. We wrote an op-ed for a venue in Spain, and I realized, “I have something here,” as I was combining those political and societal protests and issues in conversation with my own inner turmoil and frustration with the ugly things that I have seen—including with scholarly writings in early modern studies about blackness and agency. All of that came together and that’s how this book came about.

Can you talk about how the book’s form—consisting of four meditations—is different than conventional pieces of academic writing, and why you wrote it this way?

Jones: The question of genre and form was very important to me in writing this book. Writing it was very liberating and freeing, because again, there was a lot I had to get off my chest. I was also excited to figure out and document where blackness writ large pops up and manifests and becomes messy and complicated in the works of Cervantes because that has not been done before. So, I gave myself the liberty and the permission with the second book to be free, to flirt with and to experiment with different styles and forms.

I see this book as an experiment in being vulnerable and blending expectations. The form reiterates the idea and the evidence that the writing of black critics and black intellectuals is serious and demanding work. It’s a craft that is intertwined with theory and criticism, and even more so the work of black feminists. With theoretical writing and criticism within black studies, we owe a lot of that to black feminist scholars, many of whom were also black lesbians. I would say that that’s very important, and the form of this work is me paying homage to and working with that. It also represents a deeper, more sustained, careful, and committed way to engage with blackness in these early modern texts. That’s something that I didn’t necessarily do in the first book.

Another important takeaway with this book is that I want it to resonate and be accessible. Obviously it fits in academic publishing and scholarly publishing, but I hope that the book is legible to and resonates with general broader audiences. I hope that there are elements of this book that a reader who picks it up can see and connect with.

You write about “charting new methodological and theoretical terrain and possibilities” in this book, particularly with the namesake concept of Cervantine Blackness. Can you tell us about this concept and how it’s adding a critical lens that has been missing from your field before this?

Jones: I created and understand the concept of “Cervantine blackness” to merge the beautiful things about Cervantes’s writings. Because when we read Cervantes’s writings, whether it’s the Quixote or it’s his short stories, Cervantes played around with form. A lot of times he didn’t abide by certain conventions that were expected by his peers or during the time period. So in many ways, it’s a nod to that.

This book Cervantine Blackness is also for me, methodologically speaking, a platform to be creative, to be irreverent, to be vulnerable. I was just reading a review blurb for the book, and one of the endorsers described the book as a homily, as a sermon. And even though I didn’t think of it that way while writing it, when stepping back and reflecting, the meditations definitely represent and embody a form of a sermon. It’s a preacherly text perhaps, in which I’m thinking about literary analysis and literary form, and asking, “what are the limits in the bounds of the essay as a form? And how can one ponder upon and get lost in the beauty of writing and the beauty of literature and the beauty of criticism, as well?”

I didn’t want to write a book that was on the nose and very dryly says, “Oh, these are the black people that Cervantes writes about.” I didn’t want to do that. Giving a different flair and life to Cervantes’s writing is, I think, very important. Because in Shakespeare studies, for example, both specialists and non-specialists of Shakespeare have for a long time grappled with race and specifically racialized blackness. Othello is a classic example. But I would say that within Cervantes studies, that has sorely been missing, and so this book also fills that need as well.

Can you talk about your engagement with Cervantes’s texts and this concept of Cervantine blackness, and where you applied this new lens?

Jones: Absolutely. One of the characters in Cervantine writing that has excited me the most is a black eunuch named Luis. The third meditation, titled “Rethinking Luis,” is all about him, this man who I read as one of the protagonists and central figures in Cervantes’s short story El celoso extremeño. The English title is The Jealous Extremaduran.

Luis, as we’re told, is an old black eunuch. And in this meditation, I’m diverging and departing from what many famous and well-respected Cervantes scholars have read this person as, as being a slave to his own devices: music and alcohol. I wanted to obviously give a different flair and life to this character, and that required not only an in-depth, close reading of the story, but also doing a lot of cultural and social history of the eunuchs and black guitar players during the 15th to 17th centuries in Spain and Portugal. This meditation is giving life to Luis’s movements in the text by thinking about the black Mediterranean as a framework, as a space, as a concept.

There’s also a section in the meditation where I deep dive into queerness and queer studies, which for me is very important. There are clear moments where gender is fluid and flexible in the ways in which Cervantes describes and talks about Luis’s body, his interactions with other characters—both male and female—in the work. So that’s one character who I’m very excited about.

The fourth meditation—which isn’t explicitly about Cervantes but instead covers the writings of a woman writer from 17th century Spain by the name of María de Zayas—was another moment that was really fun to write. With the Zayas chapter, I’m asking the question, “what does Cervantine blackness look like, or what does it not look like, when aristocratic, high-born white women describe and write about enslavement and interracial unions and interactions?”

For me, instead of going back to agency, instead of saying that the black people who she writes about demonstrated agency and resisted and fought back, I found it more compelling and interesting and historically accurate to dig into and uncover this concept of interracial intimacy, because in her works, where black people appear they’re paired with a white “companion,” so to speak. And so we find those pairings really fascinating and rich in their messiness—and for me, the very clear violent and racist depictions that Zayas brings to her texts about black people. It was interesting to think about interracial intimacy and to chip away at what she’s doing and what these texts are suggesting, and what they are historically frowning upon and disputing in 17th-century Spain.

Zayas’s work is often read as an elaboration of the content, styles, and themes of Cervantes. As such, that’s why I named the fourth meditation “Cervantes Unhinged,” because that’s one of my claims and arguments: that Zayas unhinges—she undoes, she goes against—the nuance and the complexities and the ironic moments that are so characteristic of Cervantes and his style and his writings.

The FAS Dean's Office announces new books to the FAS community and beyond. FAS faculty can inform us of their book’s publication through this webform.