Cynthia Zarin’s New Novel Weaves Memories of Winter

May 15, 2024

May 15, 2024

By Natalie DeVaull-Robichaud

Cynthia Zarin, Senior Lecturer in English in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, discusses writing Inverno and the way characters remember – and misremember – their lives

When Cynthia Zarin was in second grade, her classroom followed a daily ritual: for ten quiet minutes, the children would draw pictures as Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons played in the background. Later, as Zarin wrote Inverno – “winter” in Italian – she chose the novel’s epigraph from Vivaldi. It was only as the novel was about to be released that she remembered those quiet minutes listening to The Four Seasons. The memory, she explained, had been there, all along.

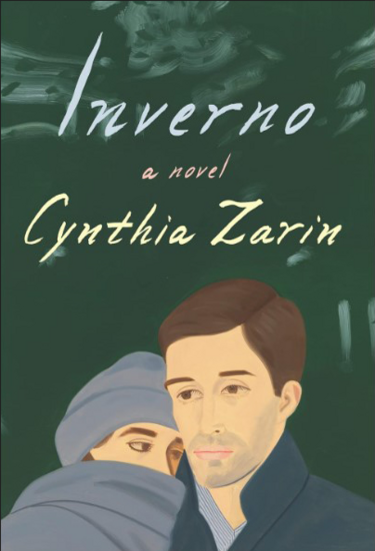

Zarin’s Inverno (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux) is a brilliant and innovative novel of memory. The novel’s prose seems to mirror the thoughts of the characters, Alastair and Caroline, as it follows the way they remember or misremember their world and each other through many winters.

Cynthia Zarin spoke to Natalie DeVaull-Robichaud of the FAS Dean’s Office about her writing process, how teaching at Yale inspired her to write novels, and the ways memories and stories shape our lives.

What brought you to write Inverno?

Zarin: At Yale, I teach poetry and nonfiction writing, and I coordinate the Creative Writing Concentration within the English Department for senior English majors who choose to do an independent project – a collection of stories, a play, a collection of poems, a nonfiction essay, or a reported piece. Gradually, I’ve been moving into all the different genres, and indeed I teach a course in the fall called Writing Across Literary Genres. I’m interested in thinking about why does one idea become a poem, why is another a short story, or an essay, or a play? Of course, there’s no answer for that, but it’s interesting to see the different achievements of the genres. It’s a wonderful course – we think about these questions together. But I was never a writer who thought, I’m going to write a novel. Next Day, my new and selected poems, is coming out this summer, and I’ve written books for children. I’ve done a good deal of reporting and cultural criticism, mainly for The New Yorker, but writing a novel just hadn’t occurred to me. Now I am in the last stages of writing a second novel, and I’m even more convinced I don’t know what a novel is. But I’m not sure anybody really does – it’s simply a way of telling a story.

About a decade ago, I started to write a very long letter to a friend. I decided to write 750 words a day, and then a thousand words a day. I just kept going. Along the way, I began to make up stories, and it ceased to be a letter. It became a long, winding snarl of prose. I really had no idea what to do with it.

I tried this and that, and I showed it to friends, including my colleagues in the English department, who said, well, it’s not a book! In the meantime, I was teaching full-time and writing theater reviews and book pieces for The New Yorker. And then a friend of mine, Leanne Shapton – who’s a brilliant artist and writer and now the art editor at The New York Review of Books – looked at the manuscript, and said, “Why don’t you stop trying to put it together and take it apart?”

So I took all the stories apart, and then I started to piece it together. And I have an extraordinary agent in London, Luke Ingram, and we sat in a restaurant in Sloane Square near The Royal Court Theatre and we drew the structure of the novel on a napkin. I think every writer has to have someone who believes that what they’re doing is something. And he did believe that, and that gave me the impetus to finish it. And I was so fortunate that Jonathan Galassi at Farrar, Straus, and Giroux fell in love with the book.

The novel follows the way memories unfold in characters’ minds. Some memories reoccur – such as Caroline waiting in the snow and Alistair cutting the roots of the locust trees in Central Park. Why do some moments in characters’ lives weigh more heavily than others?

Zarin: To me this is a very odd personal book, and I have been astonished how many people feel that somehow parts of it depict their own way of thinking or feeling. I’m very moved by that.

There’s a wonderful book by the psychiatrist and writer, Adam Phillips, called Attention Seeking. In it he says that often the things we don’t pay attention to are more important that the things we are paying attention to, which may mask what we don’t, or can’t see. I think we all do that. Out of knowing and not knowing, we construct a self. And I think Caroline does that.

I remember years ago in New Haven I asked a psychiatrist friend of mine, “How do you keep the stories straight?” I was thinking of patients coming into his office, one after another. And he said, “Stories are how we keep things straight.” I think that the relationship between Caroline and Alistair, in some ways, is crucial to Caroline, but it’s also masking another story. Why is she in that relationship to begin with? Why are Caroline and Alistair so attached to each other? The book tries to unfold that.

I was giving a reading the other night, of Inverno, and someone asked, “Well, why is Caroline trying to save Alistair?” And I said, “Well, to Caroline, Alistair is the whole world.” I think we’ve all had relationships like that, when the whole world, at some point in one’s life, is another person.

References to stories, poems, film, and popular culture weave in and out of the narrative. What effect do these touchstones have on the characters and the way they perceive their lives?

Zarin: For many of us, the books we’ve read have had as much of an effect on us as our families or our friends; these books – or films, or plays – have been ways for us to understand and even shape our own experience. I was out to dinner with some colleagues the other night, and within the first five minutes, there were 15 references – to Shakespeare, to a film, to Henry James, to Kerouac. That’s the kind of mind that Caroline has: one thing reminds her of something else. Some of the lines in the book are misquoted – the copy editors developed a sense of humor and said, “Caroline’s just misremembering that line from Eliot. Right?” And I said, “Right.”

In Inverno, Caroline goes to the movies all the time: she wants to see someone else’s story. But then she projects her own life onto the characters; the film’s complications become, illuminate, or mirror her own complications. Caroline remembers many things, but she’s also evasive. One of the lines that’s quoted in Inverno is from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, when Etta Place says about dying: “I’ll skip that scene if you don’t mind.” But, of course, we can’t skip those scenes. She knows that.

How has teaching at Yale influenced your writing life?

Zarin: I’ve been teaching at Yale for about fifteen years. I’ve been so fortunate in my students and in my colleagues: we have a very vibrant community. And if I hadn’t taught students who were also writing fiction, would I have seen my way towards this book? When I was at Harvard, as an undergraduate writing poetry, I had extraordinary teachers, among them Robert Fitzgerald and Seamus Heaney. And it seems to me that in whatever small way I can, it’s part of my work in the world to address that quality of attention I received, to my own students. It’s a privilege to do so.

What are you hoping that readers bring to and away from the novel?

Zarin: I always say to my students, “Your first reader is yourself. Is this something that interests you? Test it by reading your work aloud.” When I write, I have three or four readers in mind – some living, a few dead – who have a kind of critical acuity I try and mainly fail to satisfy. That Inverno seems to have been absorbing to different kinds of readers perhaps proves what we already know – that the basic human experiences are shared: falling in love, falling out of love, making a life. My editor, Jonathan Galassi, says everybody has an Alastair or is an Alastair!

Caroline and Alistair only meet in the winter until the very end of the book, but the novel that I’m working on now – which is in the first person, narrated by Caroline – is called Estate, which means “summer” in Italian. It is a kind of mirror, of Inverno, and takes place in warmer weather.

Cynthia Zarin is Senior Lecturer in English in FAS. Her book, Inverno, is available from Farrar, Straus, and Giroux; Next Day: New & Selected Poems, will be published by Alfred A. Knopf this August; her second novel, Estate, is forthcoming from Farrar, Straus, and Giroux in September, 2025.

The FAS Featured Books series announces new book publications by FAS faculty members to the FAS as well as the wider community at Yale. FAS faculty can inform us of their book’s publication through this webform.