By Abiba Biao

To nominate an FAS faculty member to be featured in this series, please email fas.dean@yale.edu

Bhart-Anjan Bhullar remembers well his first research trip as an undergraduate student at Yale. Each time he looks at the picture framed on his desk, he is transported back to Mexico City, back to the now closed “El Refugio” Fonda and to lavish meals spent deep in conversation about the history of life on Earth. What he remembers most, however, are the people who helped to foster his curiosity and encourage his academic interests that would later launch his academic career.

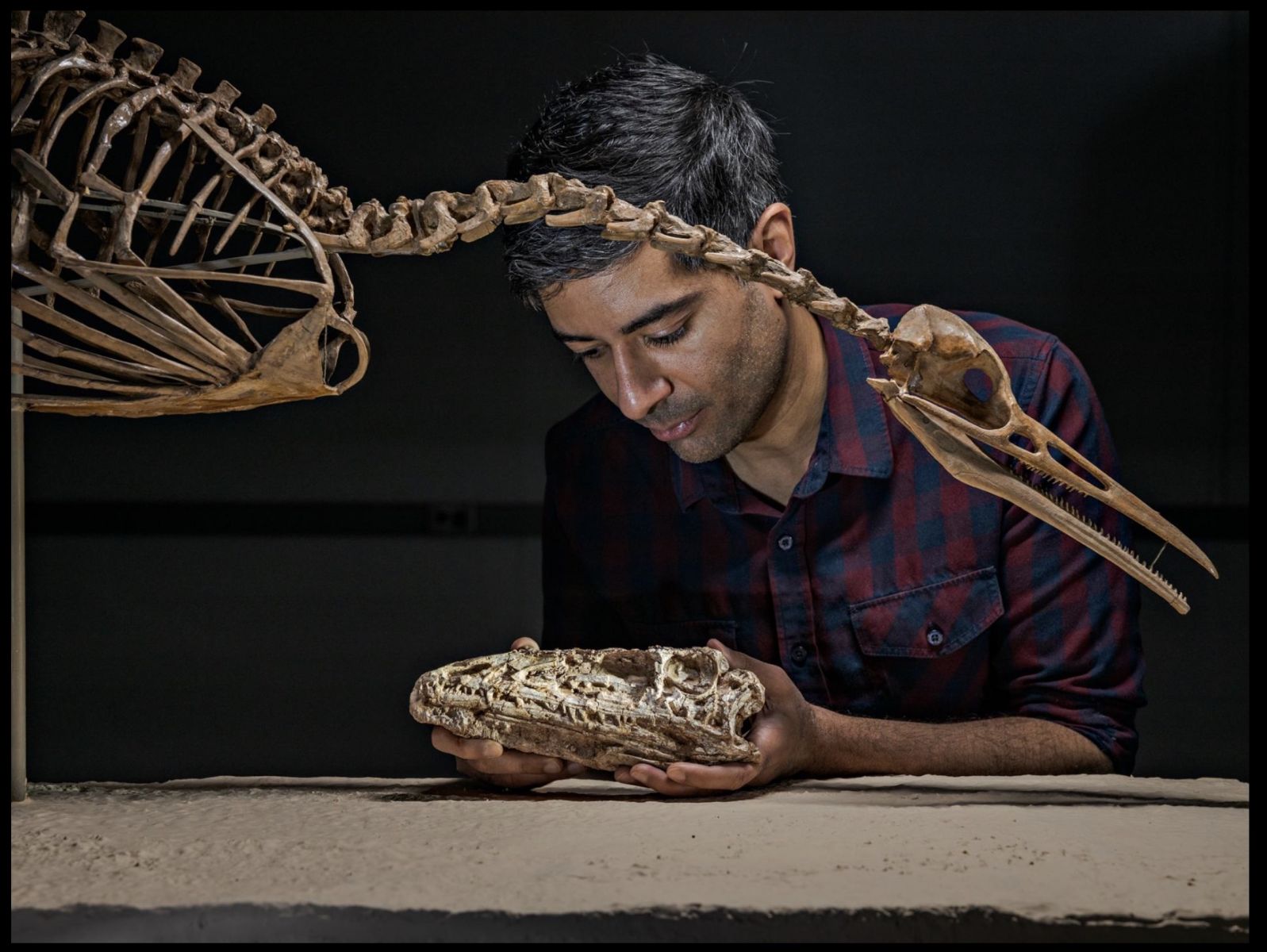

Bhullar is Associate Professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences in Yale’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences and Associate Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology and Vertebrate Zoology at Yale’s Peabody Museum. He specializes in vertebrate paleontology and vertebrate evolution.

Bhullar had always had an affinity for the sciences. But while AP Biology was his favorite class during his high school years in Kansas, he also had a passion for literature, history, and anthropology. Bhullar’s undergraduate days at Yale fueled these passions and he sought opportunities to study history and culture even while majoring in biology.

It was during his Christmas break in 2002 while looking for spring semester classes that he stumbled on a graduate course called “The Evolution of Lizards” led by vertebrate paleontologist Jacques Gauthier. As an undergraduate, Bhullar needed to convince Professor Gauthier to allow him to take the graduate-level course. Fortunately, Gauthier was more surprised than skeptical.

Associate Professor Bhart-Anjan Bhullar (National Geographic/Paolo Verzone)

To Bhullar, paleontology offered a way to do science that lent itself to a grand narrative in the best humanistic tradition.

“When I came here as an undergrad, I had to really decide whether I was going to go into English, or go into science,” he said, “but I found that there’s a way in which the story of life’s history is the greatest story there is, and it’s a true story.”

In Gauthier’s class, Bhullar got to travel to Mexico City to examine important early reptile fossils. It was a trip that he described as “a quintessential kind of Yale experience,” characterized by academic curiosity and interdisciplinary collaboration. There he tasted the best food of his life, developed a relationship with his future colleagues, and fell in love with vertebrate paleontology.

Drawn in by the class and the intelligence and affability of the graduate students in paleontology (a field in which Yale has long been a, if not the, global leader), he joined Gauthier’s lab, where, he says, he always “felt at home.”

From there, Bhullar earned his M.S. in Geological Sciences at UT Austin in 2008 and his Ph.D. in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University in 2014.

Bhullar returned to Yale in 2015 to serve as Assistant Professor of Earth & Planetary Sciences and Assistant Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology and Vertebrate Zoology at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History and was promoted to Associate Professor and Associate Curator six years later.

Despite his time away, Bhullar never forgot the generous and collaborative culture at Yale. It was this environment which brought him back: he wanted to mentor students alongside the same faculty that mentored him.

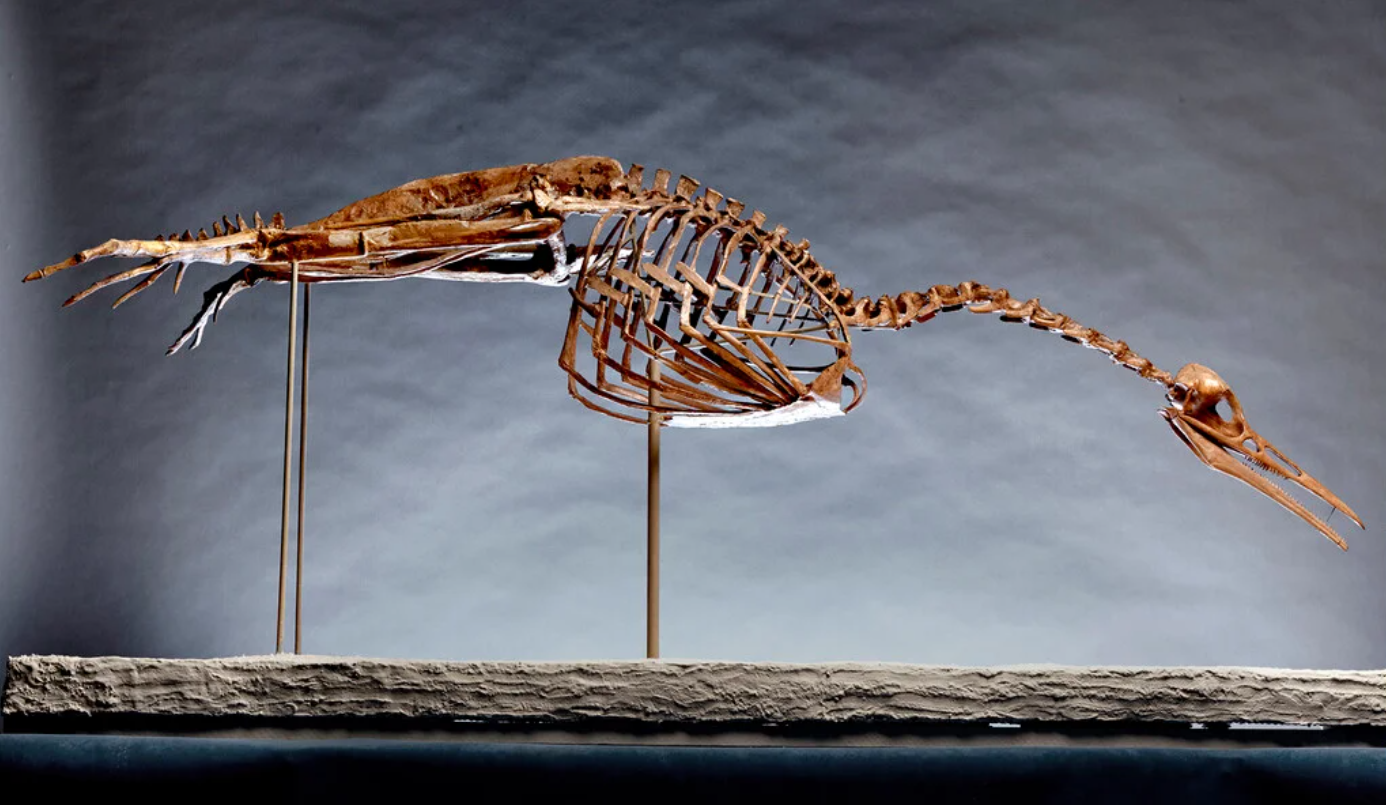

The fossils of Hesperornis, an 85-million-year-old bird that had the earliest modern bird beak. Hesperornis had teeth in both the lower and upper jaws suggesting that the toothless beaks today’s birds have had not yet appeared in Hesperornis. (Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History/Robert Lorenz)

Today, Bhullar’s lab studies the evolution of vertebrate life. They examine major evolutionary transitions using both the fossil record and laboratory-based developmental biology.

“Most of what we ‘are’ was shaped not when we were people, not even when we were apes, not even, in some ways, when we were mammals, but far, far back when we were more like tiny lizard-like things running around, or, earlier still, like fishes” he said.

From humans to the smallest birds in the sky, today’s vertebrates descend from what Bhullar calls “success stories.”

“What interests us in my lab is how those great success stories came to be and what happened, not necessarily during the full flowering of their success, but during that early period [of evolution].”

One of his most notable research projects focuses on the development of bird beaks. By examining living birds, their embryos, and transitional fossils, Bhullar and his lab discovered several defining evolutionary and developmental features of this evolutionary “key innovation,” among them the fact that beaks originated first as pincer-like grasping organs or “surrogate hands.” Other major contributions have covered such disparate topics as the neurobiology and sensory acuity of ancient organisms and the evolutionary and developmental transformations of the leg and pelvic girdle within reptiles, including birds. “We’re studying just about every part of the vertebrate body in some way,” says Bhullar.

“Some of the fossils that are still embedded in rock are so delicate, you can’t really prepare them,” he explained, “but you can put the rock in a CT scanner and digitally remove [the fossils] in three dimensions and then put them back together in virtual space. This creates a digital reconstruction of the organism.” The Bhullar lab has developed techniques to perform a similar sort of 3D digital processing of embryos and the molecules they express, winning in the process several major imaging awards.

Paleontological studies at Yale are unrivaled due to the resources and infrastructure available here, including a CT and micro-CT scanner facility and laboratory spaces fitted with a complete molecular developmental lab with cell-culture facilities, in addition to the vast collections of the Yale Peabody Museum itself, to which faculty and students add every year by collecting fossils in the field. It is this support that allows for such consequential discoveries. The stories Yale paleontologists uncover are incorporated into the narratives they teach in courses such as EPS 125, The History of Life, which Bhullar co-teaches with fellow paleontologists Derek Briggs and Pincelli Hull. Bhullar’s lectures for EPS 125, which interweave the story of life on the planet with metaphors and comparisons from human history, literature, and mythology, were a major influence on narrative of the Steven Spielberg-produced Netflix miniseries Life on Our Planet, on which Bhullar was primary outside scientific advisor.

Advance screening of the Spielberg-produced Netflix miniseries Life on Our Planet, held in Yale’s Marsh Hall

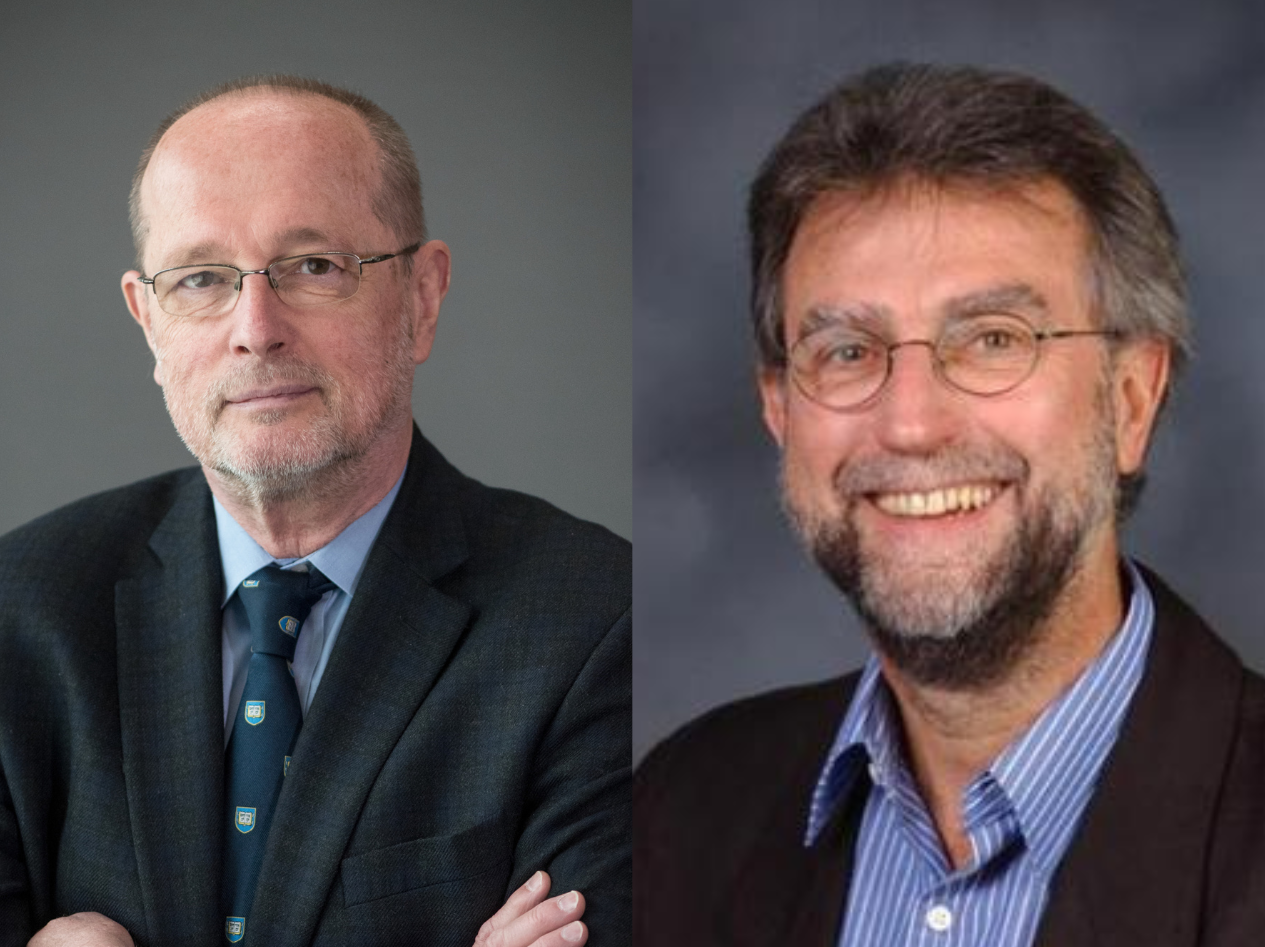

Just as he studies the foundations of life in his lab, Bhullar recognizes the mentors and figures that have breathed life into his work and helped him evolve into the person he is today. Alongside Gauthier, Bhullar credits retired professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Günter Wagner and late paleoanthropologist Andrew Hill as brilliant mentors.

“Jacques, Andrew, and Günther, for me, were just archetypal Yale professors. They were, [and] are, so generous, so gentle, and such magnificent teachers,” Bhullar said.

Now Bhullar wishes to impact his students in the same way he was influenced by his mentors, taking note of their teaching style and compassion, which he hopes to embody in his own life and pedagogy.

Bhullar commemorates Andrew Hill not just through his work, but in his personal life, too. Hill was a fan of Abyssinian cats, and Bhullar adopted one of his own on Hill’s recommendation: “I asked him whether they were good cats, and he said, ‘you must get one.’” The cat’s striking feline face adorns the lock screen of his phone (Hill famously had portraits of his two on his office desk).

“His example of how to be a human being has informed me now as I try to be a small part of a modern Yale whose fundamental character is that of the place I knew and loved,” he said.

Retired professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Günter Wagner, and late paleoanthropologist Andrew Hill, J Clayton Stephenson Professor of Anthropology.

Being a junior faculty member can be challenging and stressful at times, but the people at Yale constantly support him and remind him of his capabilities.

“The dean’s office, the provost’s office, and my wonderful department have been nothing but supportive,” he said.

To Bhullar, Yale embodies the spirit of giving: giving back to students, to teachers, and to the surrounding community. He wants to continue this cycle set forth by his mentors and pay forward that generosity to his students and postdocs by cultivating their interests and giving them room to foster their own biological work. Indeed, despite his lab’s being relatively young, its members have gone on to tenure-track faculty jobs at major institutions across the world, including Princeton, Cambridge, and Johns Hopkins.

“The philosophy I learned from people like Andrew and Jacques is that we have something to give,” he said. “We’re here because people have given to us and so we’re going to give as much as possible while maintaining a strong program for the benefit of future students and scholars.”